Golden Students

or

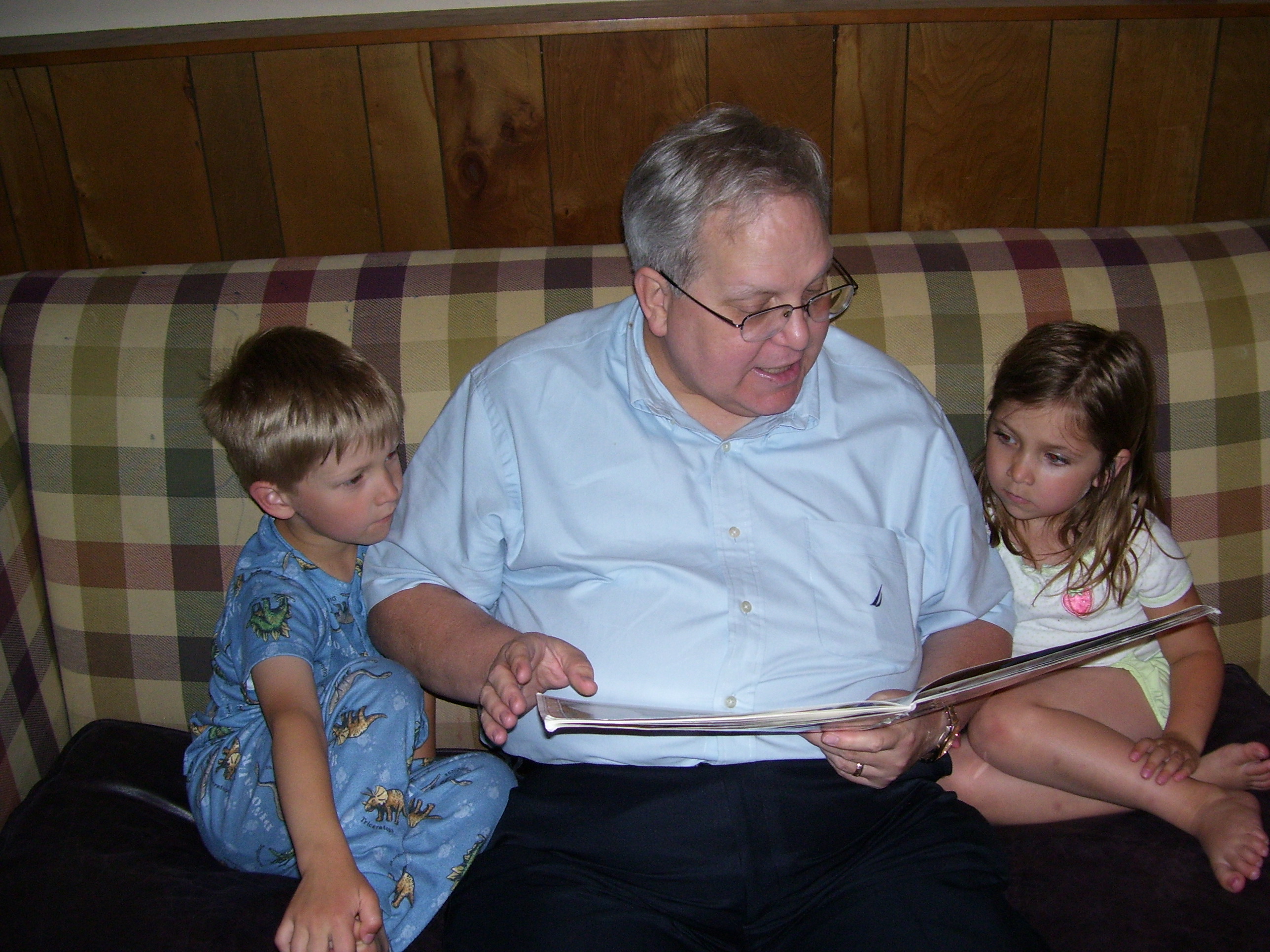

W learning very early the importance of education

Two weeks ago, W and I were sitting at the kitchen table, talking through her AP Human Geography Packet answers. She’s been struggling to keep her grades up in that class, so Steve and I have been doing a little more intervention. We’ve been monitoring her homework in that class. We never, ever monitor her homework. But this is a “college” class, and will count for “college credit” if she passes the AP exam. It will also permanently affect her transcript when she applies for college, so we decided we better see what’s going on. Our first strategy? having her read her homework responses to us and talking through them together.

W scrolled through her computer screen and read her first written response aloud with a lot of confidence. “….because it is relevant,” she said proudly, sitting back in her chair after she had finished explaining her answer. I could tell that she was particularly happy with her word choice. “Relevant” is a rather smart sounding word.

“I think it sounds really great,” I answered. “I liked these two pieces of information here you included. Now can you tell me why this is so important. Why it’s relevant?”

I call it the “so what?” factor–or, more gently, the “tell me why this matters” factor. I’ve tutored English to a few high school students and taught college-level English classes off and on over the last seven years. It’s hands down the hardest question for students to answer. And just like W, most of the time their writing is usually descent. They can find information and regurgitate it into their own sentences. It’s the synthesizing part–the true understanding of the information–that they have a really hard time with.

“Because it’s relevant,” she said with a big, angry sigh.

“But why does this matter?” I tried to say gently. Talking to a fourteen-year-old is always a delicate matter. Talking as the mom of the fourteen-year-old makes it even more tricky.

“It just is,” she snapped back.

“Okay, but look at these two points here. What do you see in the world right now that’s similar? What if you included some of your observations into–“

“You’re trying to change my writer’s voice!” she said, packing up her laptop. “I’m going to talk to dad about this. He teaches college classes.”

I was really proud of myself. I didn’t say anything back. Even though I really, really wanted to.

A few minutes later I heard W and Steve discussing the issue downstairs. Sure enough, he asked her the same question. Sure enough she pushed back. But over the next few nights of reviewing her AP Human Geography responses together, she started to get the hang of it–at least understand what AP level responses should look like.

I feel like we’re helicopter parenting W more and more recently. And if you’ve been following our lives on this blog for the last few years, you know that she is definitely our “free-range” child. We have always been so busy and consumed with helping J, that for her entire life she’s been on her own to be responsible, do her homework, and figure out how to get help for her homework questions if Steve or I are busy. And she’s been really good at that. But this is grade 9 now and everything counts. So we’re intervening more. We’re calling friends for help with science the night before a final. We’re talking over AP HUG responses. Every night now Steve and I are tag-teaming between J and W for homework help from the time we finish dinner until the time the kids are in bed.

It’s exhausting. And it’s a good thing we “only” have two kids. Because I have no idea how we’d be able to help anybody else when we’re working non-stop between the two of them. And it’s kind of ridiculous but at the same time absolutely necessary.

Because being a good student in high school is really stressful. Getting into college is high stakes. W already knows that and stresses out over her grades all the time. She’s checked out admission acceptance rates

and the average GPA and ACT of colleges (specifically BYU–where Steve and I both got our undergrad degrees and where she wants to go). She’s researched the types of classes recommended for a good application. She’s done it all on her own because she’s a high achieving student.

The more we talk about it (and find out what the process looks like today instead of 20 years ago) I think it’s absolutely ridiculous. AP classes in high school are absolutely ridiculous. Does a 14-year-old ninth grader have the mental maturity and life experience to understand and comprehend university-level information the same as an 18, 19, or 20 year old? No. Freaking. Way. And most 15, 16, and 17 year-olds (even the smart, high achieving ones) don’t have those skills and maturity either. But AP classes are an indicator of “smart” kids and the more you take the better. It’s the way to play the college entrance game (because it is a game–how many AP classes you take, how many extra-curricular activities you are involved in, how many service organizations are you involved in are prerequisite indicators of acceptance). The ACT is another part of that game. Taking Kaplan classes to learn how to take the ACT to get the highest score is another part of that game. It’s ridiculous. And acing these requirements and checking those boxes doesn’t mean that you’re college material. I’ve seen many of those “high achieving” students struggle in my freshman-level classes because somehow along the way they didn’t learn how to develop those higher-level thinking skills. They’ve learned how to jump hoops, not how to think.

Honestly, I don’t get the push behind AP classes in high school. If we want to give students a challenge, then put them in learning appropriate classes that will challenge them and teach them those higher level thinking skills they need to learn to start thinking like a college kid. “Standardize” those classes if you want to. Give those classes a special letter or asterisks so colleges can look at transcripts and identify those “high achieving” students. But let’s not pretend they’re taking college classes and thinking like college kids in high school.

There are so many other things we expect them to manage on top of navigating their social lives (I would argue this is an absolutely necessary part of human development that helps them become better adults in the future. This skill is another make-it-or-break-it college skill to learn too, but we never talk about it). They already have to jump through standardized tests and learn all the Da Vinci code secrets in order to score well on those tests. At 14, 15, and 16 that’s a lot of stress to handle. And many of them use unhealthy coping strategies to survive that stress. Many of them see news like this about the University of Florida–a state school–not an elite or private university and feel even more pressure to succeed:

“The university received a record amount of applications at more than 41,000, which resulted in a more competitive class. The test scores and GPA of students admitted into the new class proved to be higher than previous years.

The more than 14,000 students who were admitted for Summer B and Fall had an average GPA of 4.45, average SAT score of 1388 and average ACT score of 31, UF spokesperson Steve Orlando said.”

Does this system really work? Does it really prepare students for college? I’m not sure. I just see a bunch of high stressed kids who are feverishly obsessed with checking off the boxes so they can have the right opportunities. Missing the joy of learning–the point of learning in the mean time.

I guess, as much as I disagree with the system, we’re going to be a sucker to the system too. This week is the last week to sign up and pay the fee to take the AP test. We’re signing up to play the college entrance game too. Because, after all, that’s the way it seems to get there.