What we remember (and how we teach our children about the world)

Bringing J to an awareness of the world–especially grown up things always makes me a little nervous. J’s brain is a steel trap for memories–especially memories that carry any pain or anxiety. J remembers things like back when he was in grade two, where the lunch ladies burnt the school pizza and set off the fire alarm while he was at gym, causing a (minor) evacuation. That was the 89th day of school and he won’t let that go. And every year since we hold our breath, cross our fingers, and go through all sorts of rituals to make it through the day when the 89th day of school rolls through. There’s a myriad little things like this J collects and stores in his brain, always remembering, always filing and pulling out those files occasionally to revisit them. To J, that’s what it means to remember.

Bringing J to an awareness of the world–especially grown up things always makes me a little nervous. J’s brain is a steel trap for memories–especially memories that carry any pain or anxiety. J remembers things like back when he was in grade two, where the lunch ladies burnt the school pizza and set off the fire alarm while he was at gym, causing a (minor) evacuation. That was the 89th day of school and he won’t let that go. And every year since we hold our breath, cross our fingers, and go through all sorts of rituals to make it through the day when the 89th day of school rolls through. There’s a myriad little things like this J collects and stores in his brain, always remembering, always filing and pulling out those files occasionally to revisit them. To J, that’s what it means to remember.

November gets me thinking of the things we do, the rituals we do to remember things. Wednesday (November 11) was Veteran’s Day (U.S.) or Remembrance Day (Canada). American Thanksgiving comes up at the end of the month too. One of the things I remember as a kid—rituals ingrained in my head—came with Remembrance Day. As soon as Halloween was over, everyone started wearing poppies. Bright red flowers everywhere. In November we learned Remembrance Day songs in music class. I remember learning “One Tin Soldier” the 1969 song by The Original Caste. I remember it because it was a ballad—a story about a mountain kingdom and a valley. It was a war song. I mean, at seven and eight we were singing about people wanting to kill their neighbours, wanting treasure (which was really peace on earth), bloody mornings. You don’t forget things like that when you’re a kid.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-wuly-XRXQ

And then there was the day before Remembrance Day at school. Where we watched old herky jerky black and white silent films of WWI and WWII footage. There was always an assembly—300 kids in a gymnasium where there was the reciting of In Flanders Fields by John McCrae followed by a junior high visitor who played a painful rendition of taps on their trumpet. And then 300 squirrely elementary kids sitting criss-cross applesauce on the floor were expected to sit through a moment of silence. Out of all the holidays and celebrations in Canada, I find it the most haunting, most patriotic, the most (almost) spiritual ritual Canadians have. And I wanted my kids to experience a little piece of that.

It’s a hard call sometimes as a parent, on what you want to expose your kids to. What are the world’s necessary evils you should teach them, warn them about, experience them to.? We’ve sheltered J and W a lot about what goes on in the “real world.” Even as an adult there’s only so much “real world” I can take before I want to shut off the TV or radio for a few months.

I wanted my kids to experience Remembrance Day—in that haunting, patriotic, spiritual way. But J has severe anxiety issues and that steel trap mind for things like this. But finally I came to this conclusion–history is safe. It’s behind you, it’s something you haven’t been through yourself, almost like reading a novel or learning the song “One Tin Soldier.” You can pick it apart and analyze it. Learn from it.

So we drove up to Winnipeg early Wednesday morning and made it (one time!) for the Remembrance Day service at the RBC Convention Centre. A cute military family sat behind us, two parents, service man and woman, telling their little elementary school boy what was going on while the black and white WWII footage was playing as we waited for the parade of flags to start the ceremony. “Who died?” The mom asked the boy. “Great grandmas and grandpas died,” the mom answers her own question.

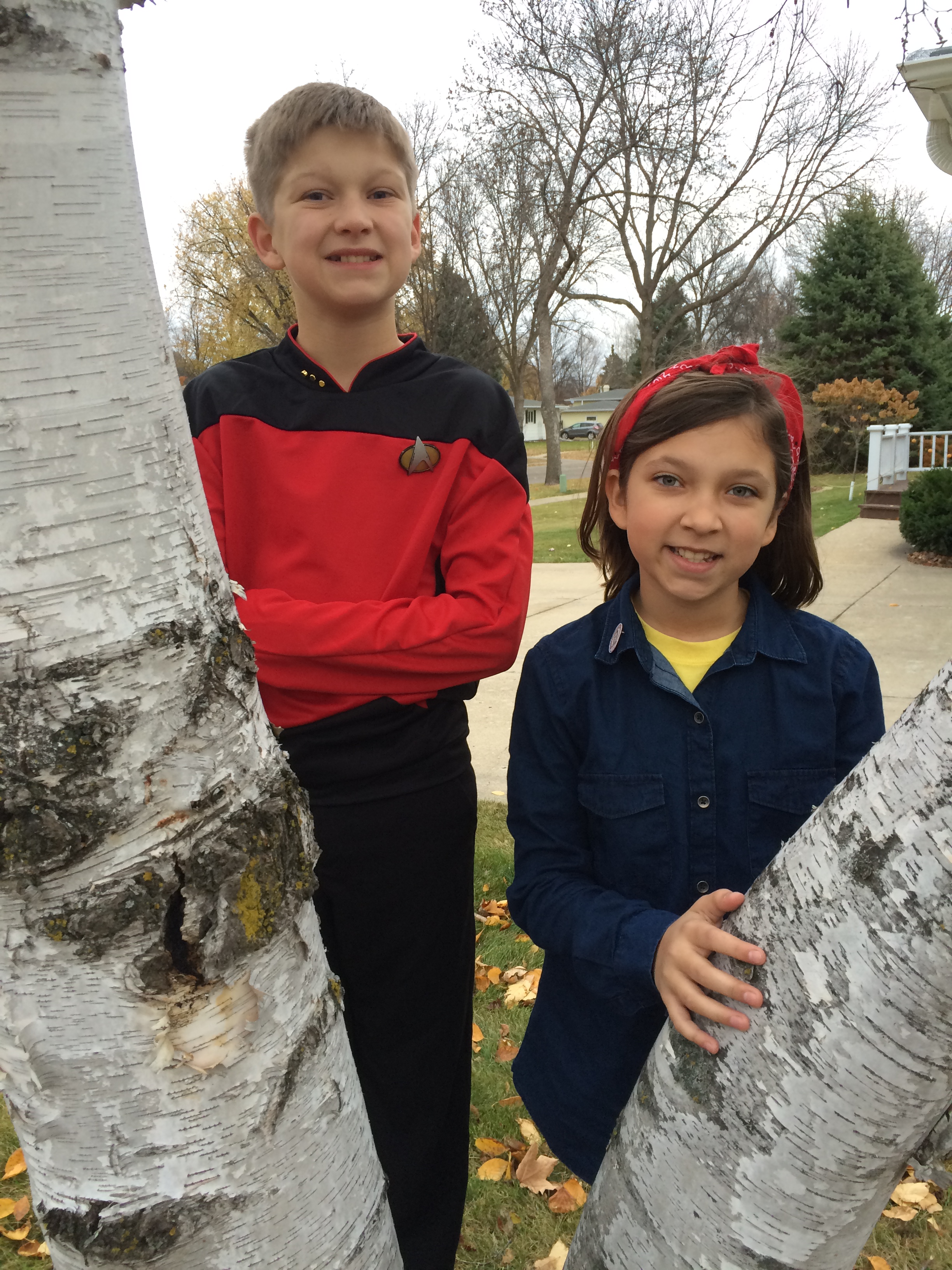

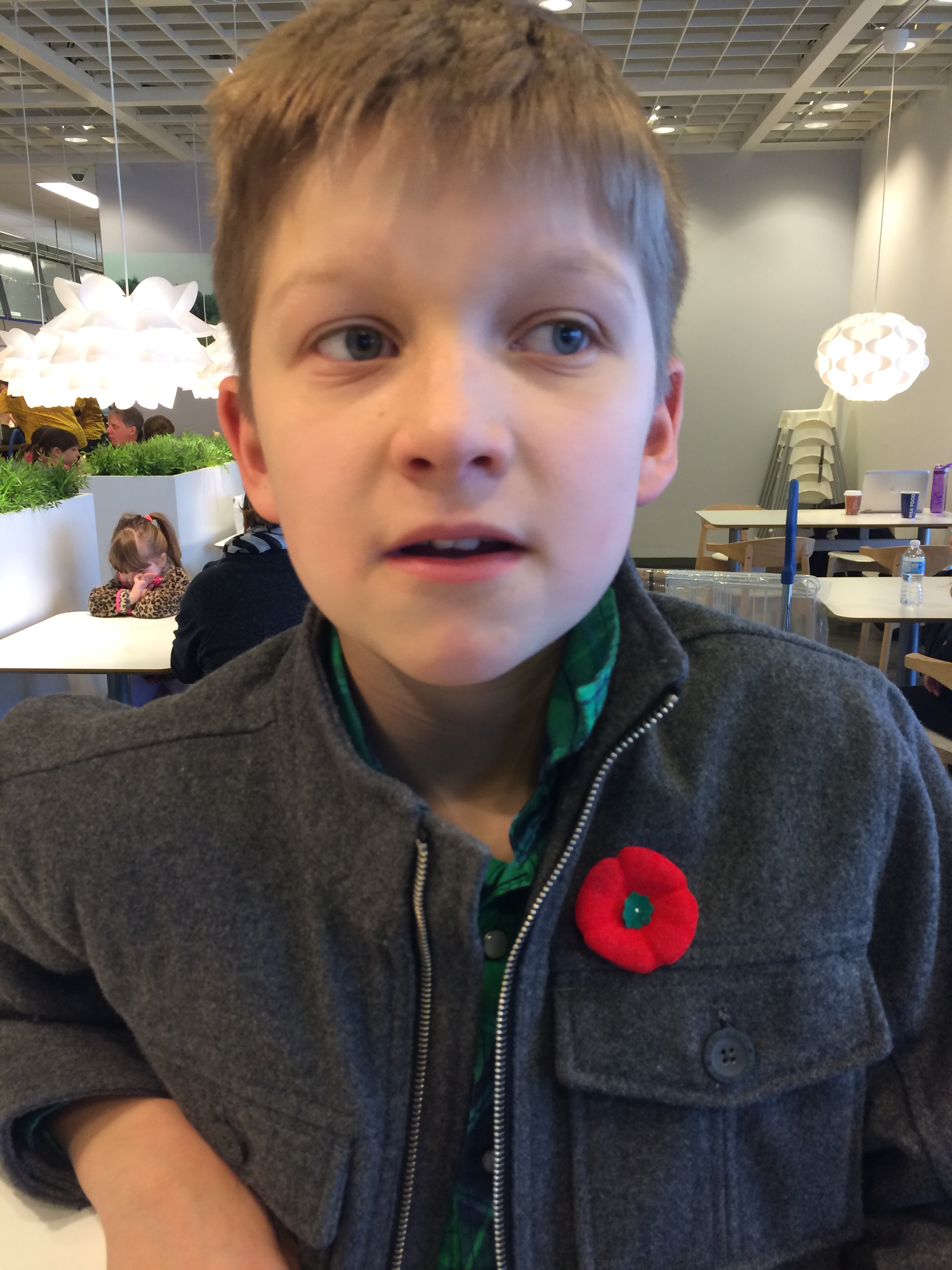

My kids got to wear poppies and we sat through the whole hour and forty-five minute service. It reminded me of a funeral, the standing, the sitting, the standing, the sitting prompted by the emcee. The placing of wreaths (which took FOREVER—all the little kids [even mine] were a quiet squirrely in their seats).

And then, while I was sweating it out, hoping my kids would be quiet and respectful until the end, one of the speakers—a WWII vet (who recalled his arrival at Juno beach with all of the horrors of war) said, “if we don’t remember, who will?”

That’s why we do this. That’s why we make our children sit still and go through these rituals. Because it IS important. It’s important to J, with all of his anxiety and rituals and (at times) paranoia, it’s important for him to learn to be still and respectful and remember. He didn’t say a word through the service. I’m not even sure how much he picked up on. But that’s okay, because I don’t know if anyone of us can really understand what happened in those wars. But we do understand this: that we need to be grateful.

These past weeks we’ve talked about refugees with the kids. We showed them this video one of my cousins posted about refugees landing in Europe. We asked them questions about “what do you think it would feel like to leave everything at home and have to move to another country without any of your clothes or iPad or games or anything?” we say, “look at these kind people helping out. Do you think you would help out like that?”

Yesterday I had NPR on in the car. My kids never listen to NPR with me, but this time J heard “Paris” mentioned and asked. “What’s going on in Paris?” He’s obsessed with geography right now. He knows Paris is the capital of France. I didn’t know what to say. Does he really need to know this? I thought, but he is asking. He’s expecting an answer.

“Some bad people hurt and killed many people in Paris.”

“That’s not good,” he said.

“No, it’s not.” I said.

Right there, in the car, J learned another step closer to empathy.

We don’t tell him about the school shootings that happen so frequently. Murders, racism, descriminiation, and violence. We try to keep him away from the heart-heavy headlines. I think he’s steel trap brain would hold on and hoard all those things.

But we’re starting to talk about the human problems and struggles. The stories that help us remember we are a human family. Because it helps us help this autistic boy understand others and ultimately himself better. to learn those lessons in empathy.

We’re asking this question more and more:

“What do you think it would feel like?”

It’s that question that helps us all remember what it’s like to be human.