To stim or not to stim

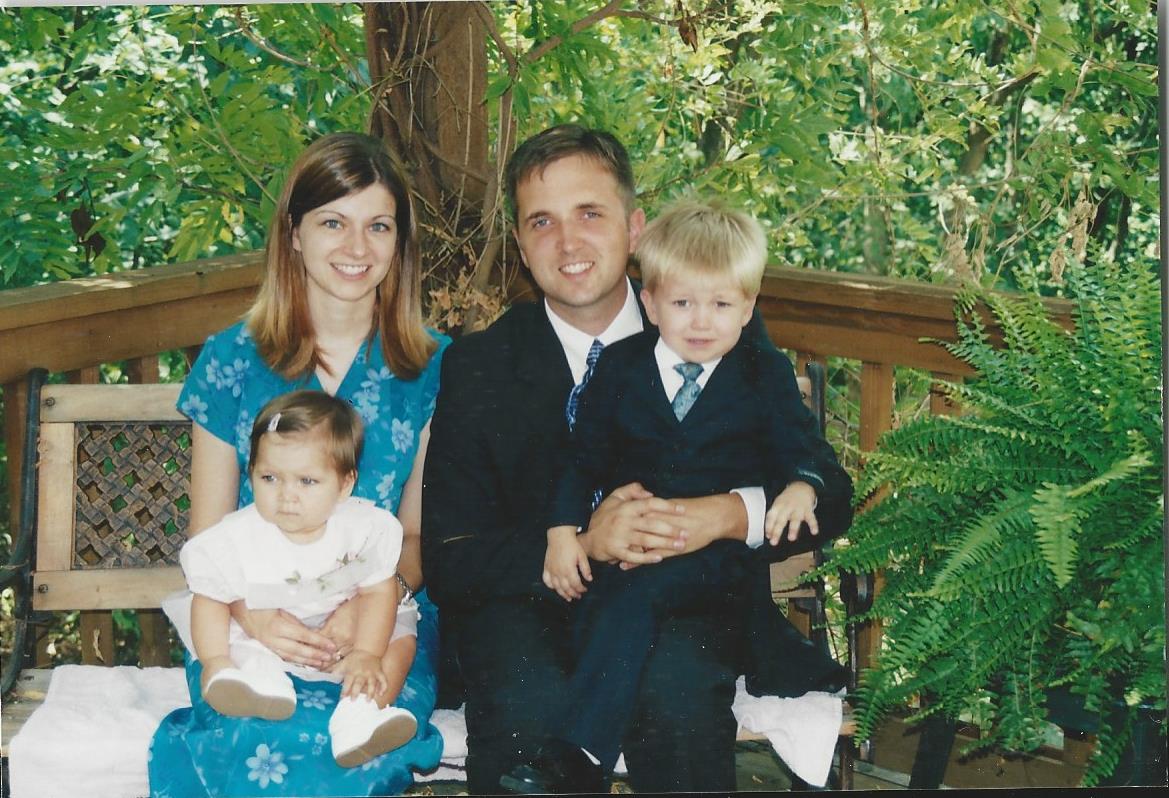

One of the first things I noticed when J was a toddler was the quirky behaviour. J liked to play games–spinning games. He liked to spin coasters, spin plastic plates, any sort of disc he could find, he would bring the disc to me and beg me to spin it. He LOVED it. He’d giggle and beg for more. He would also do this thing when we were outside, and run to the corner of our little town home in Illinois, tilt and close one eye, staring down the corner of the side of the house and run back. He’d run back and forth, giggling the whole time. I had no idea what he was looking at, but I knew it made him happy.

He’d also flap his hands a lot. When he was really excited or really mad. Just like teenage girls flail their arms when they get excited. He’d dance in circles, the same circle over and over again to Seal’s “Love’s Divine” and half-way through the song do this strange interpretive dance move when he would squat, touch the floor, and reach up to the sky. He’d do it the same way every single time.

J always had to have something in his hand. Usually a stick, a straw, a pencil. Something that could impale him if he tripped and fell. He also had this Fischer Price cheetah figure he would carry around with him all the time. Not to play with, more a security thing. He’d have a meltdown any time we tried to take either the pencils or cheetah away.

The humming and flicking of the fingers came a few years later. When you’ve never heard the word “autism” in your life before, these are all things that are sort of endearing. Part of your toddler’s unique personality. And your heart kind of swells because you think in your beaming-with-pride parent way, “my cute kid’s got character.”

And then when you find out that all of these cute character quirks your child has are self stimulating autistic behaviours (aka stimming) you suddenly hate all of them. I got embarrassed when J would walk through the store, humming to himself, staring at his flickering fingers. I’d tense up when we’d go to someone’s house and he’d make a b-line to the coasters. I’d cringe even more when a friend would spin them for him after J begged them. “Don’t encourage it,” I’d think angrily to myself. “It’s making him more autistic,” I thought. I’d pull the pencils out of his hand as soon as I caught J sneaking one and he’d be in a meltdown for the next 45 minutes. (No, that’s not an exaggeration. That’s what an autism meltdown looks like). “I don’t care,” I thought. “If you are going to be autistic, fine. But I’m not going to let you look like you’re autistic.”

Over the years, I started reading and researching and talking to other autism moms and figured out what the whole “stimming” thing was all about. In reality, every person on this planet “stims” from time to time. I used to do it in my 3rd year of university in my French 420 class that started at 2pm and lasted an 1hr and 15 minutes two times a week. It was an French art history class and the lecture was entirely in French. And my professor would turn off the lights and show us slides for most of the class period. Every class period. In order to stay awake and stay focused (because my native language is NOT French) I had a game plan. Half an hour into the class, I’d pop a piece of gum into my mouth. At the 45 min/hour mark I would get up to spit out my gum and return to my seat. If I felt like I was dozing at any other time, I’d start tapping my foot under my desk or lightly tap my pen against my notepad. Sometimes I’d push down the cuticles on my fingers. I didn’t know it at the time, but in my own way I was “stimming.”

I did what I had to do to stay alert in the class. And this is what many kids with autism do. They do those “quirky” behaviours because they’re trying to keep that balance of alertness for themselves. Unfortunately, their alertness is sort of skewed. They’re either hyper-sensitive to things (so they hum and block out noise, cover their ears, close their eyes, etc) or super anxious about something (so they flap, or hum, or run around), or under stimulated (wiggle their fingers, pick, or chew things). Since kids on the spectrum are super sensitive to their environment (more than the average person), they’re always trying to regulate their awareness balance. Suddenly, it seemed to be an “okay thing” to do. Therapists and specialists would tell me I shouldn’t be so quick to discourage it. J needed it to keep in balance. So I got softer on the “stimming” thing. Now that J is older it is pretty apparent that he has autism so I feel like I don’t have to explain the stimming as much to other people. We sort of let him do his stimming thing.

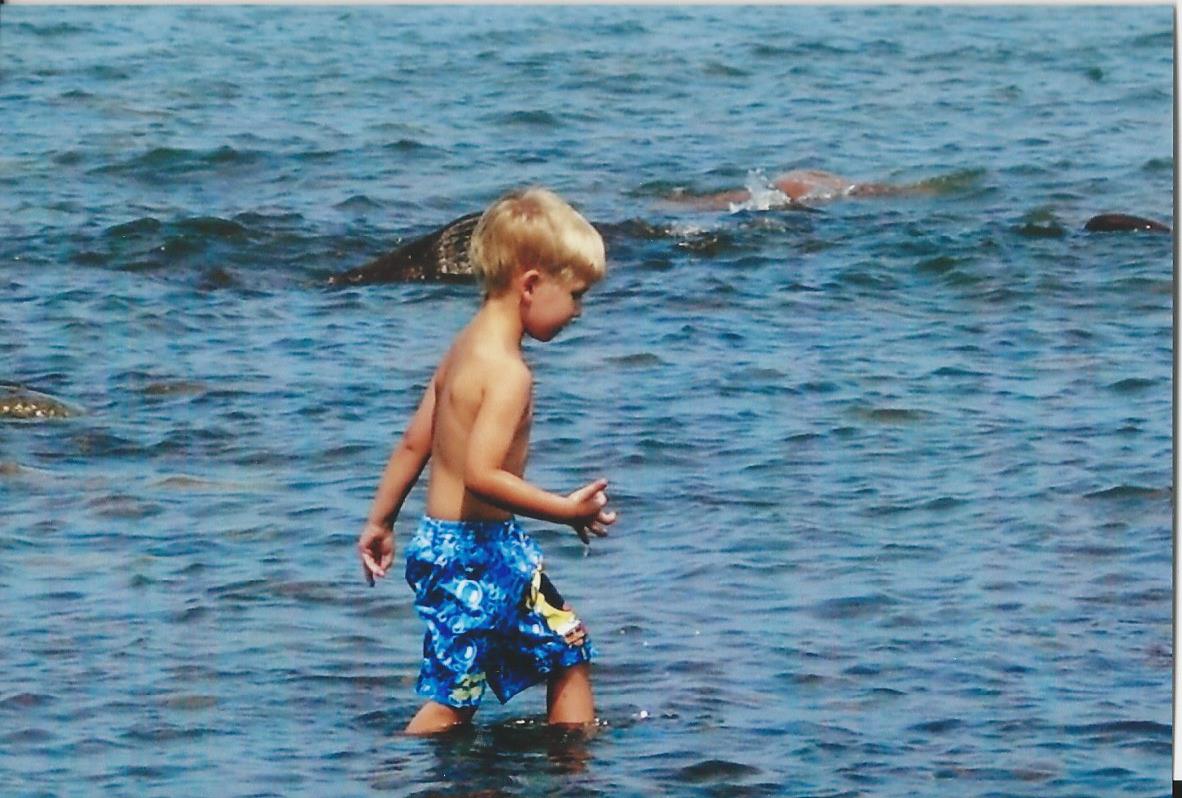

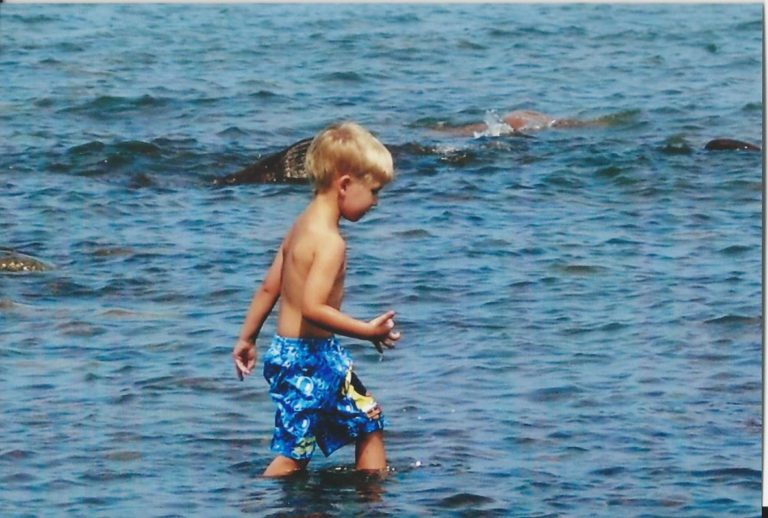

J is about 4 in this video. The stimming is really subtle. This is at Lake Superior and J is throwing rocks into the lake. You’ll see him shake/flap his hands every once in a while after throwing a rock into the water. Watching the ripples was a type of stimming. You’ll also notice it while he sings thealphabet. He’s forming the letters of the alphabet with his fingers (that’s actually NOT stimming) but you’ll see him flap his hands during the song.

But after working with him this summer, I’ve changed my mind on the stimming thing again. Yes, stimming helps J stay calm, but it also removes him from “our world” because he gets so caught up into “checking out.” Yes, J still pays attention (somewhat) to a movie, while flicking his fingers. But as I’ve been paying more and more attention to the stimming, I’m finding that he’s not paying enough attention. He does it when we work on math. He does it when we work on reading. The more I pay attention, the more I see he’s constantly doing it. Stimming is J’s version of your child’s iPhone/electronic device/video game/Netflix addiction. Sure, initially, it’s a good distraction or wind down for your kid–to check out from a busy day at school or from practice, but if they spend too much time doing it, they’re missing out on the world around them. I really noticed how much J misses out on learning because of the stimming. If he’s walking down the street staring at his fingers, he’s missing out on interacting with others. He’s missing out on observations and making inferences on those observations. He’s checked out.

Our new rule this summer has been “no stimming while working, watching TV, or when we’re out of the house running errands or at XC practice.” And already I’ve seen a huge difference with his focus in our daily “homework.” I spend less time explaining things to him when we work on math. He gets through the problems quicker. He’s making more connections when we’re “out and about.” Reminders of thinking about “your arms and hands” are good at XC too since he has really bad arm form. I really have to remind him to rein in the stimming. It’s become such a (bad) habit. He slips into it so easily and I’m so used to seeing him do it, I even forget to remind him to “stay engaged.” Yes, when he needs a real “break” he can go off and stim when he needs to. Just like when I need a break I’ll check out of the world for a few minutes and scroll down my Facebook feed. It’s a real struggle to be present all of the time–in fact, it’s hard for me to be present when I find that my “check out” time is a lot of Facebook time. But it’s so important. In so many ways I wish I had understood this stimming balance a little earlier. I’m hoping being a little more cognizant of it now can help him become more present and engaged with the world around him–and a little less anxious too. Sometimes too much stimming almost triggers his anxiety because he starts drifting off thinking about his obsessions and things that stress him out. Sort of like being on Facebook or playing video games too long?

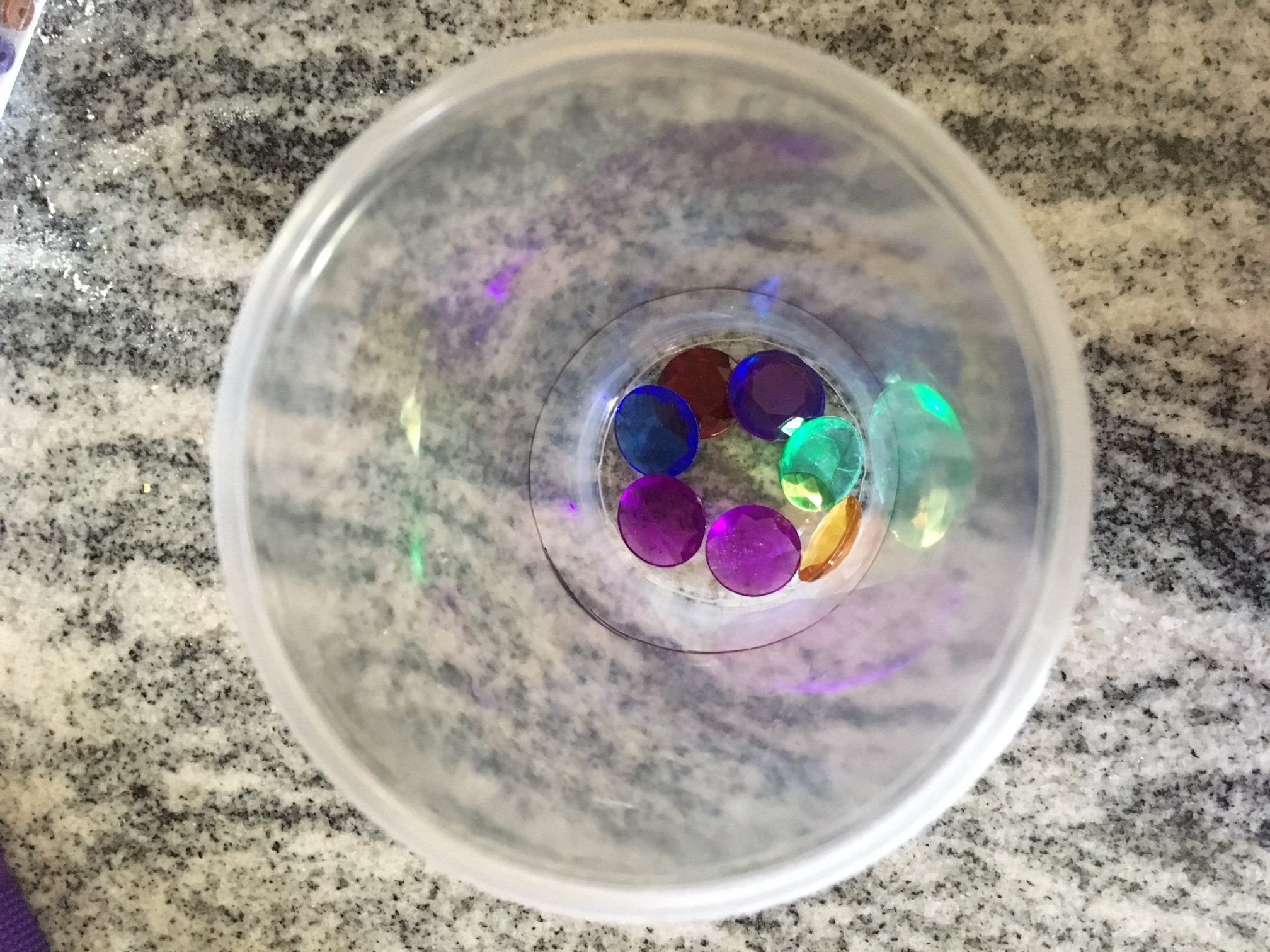

As we hit a new school year in a few weeks, this is going to be one of my priorities and one that’s going to be hard to implement, especially in the school environment. J relies so much on stimming to get through a class period. He uses his rubber wristbands or springs to flip and flick all through a class period (you know that fidget spinner craze? Fidget spinners aren’t J’s cup of tea, but the springs really are. No, this isn’t a product plug, it’s just to show you what kind of fidgets float his boat). It’s been great because it keeps him calm and quiet. But at the same time his attention isn’t where it needs to be. It’s going to be something that we’re going to have to figure out. Lots of things are changing in the next few weeks–new school, new schedule, new expectations. I’m sure my visions of reduced stimming time might be too grandiose for school right now, but it’s challenge we can continue to work on at home.

So J here’s the deal–you and I let’s both work on being more present. You cut back the finger flicking stimming, I’ll cut back my iPhone stimming. In a month, let’s see where that takes us.