This changes everything

There are very few clear moments of revelation when raising a child with autism. As a parent, the autism puzzle is always on my mind. I’m reading constantly about autism. I’ve gone through phases of intense research on ABA and Stanley Greenspan’s Floortime approach. I’ve read about Temple Grandin, read things written by Temple Grandin, have heard Temple speak on Youtube, NPR, and in person, and while all of these sources have given me a better insight into J, nothing has been a “perfect fit” solution by any means.

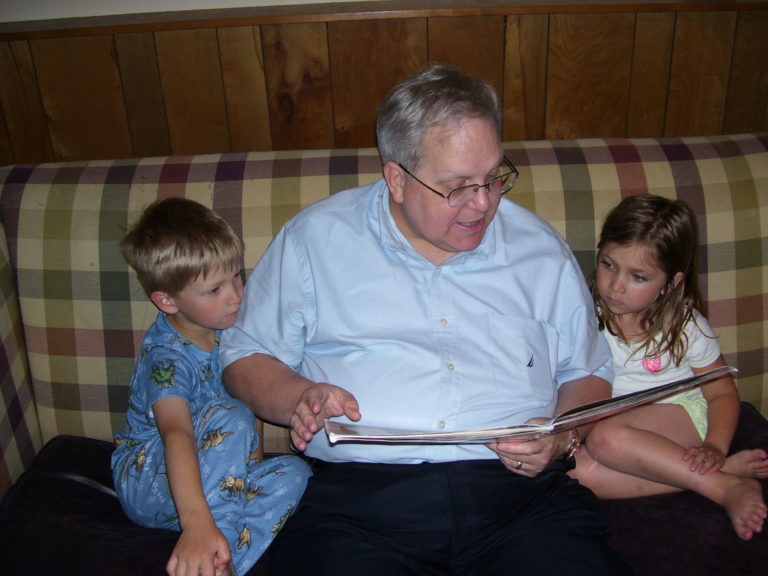

So when I went to the Lindamood Bell conference last week in Minneapolis, I wasn’t sure to expect. Because I had researched the Lindamood Visualizing and Verbalizing process before I attended, I knew a little going in. I knew that the process helps kids build pictures or a movie of the language they hear and read and that in some way helps comprehension. And I was really intrigued. Because Joshua has incredible phonological processing (knowing his letter sounds and blends) and incredible orthographic processing (recognizing that letter sounds and blends connect to symbols called letters on a page). He just has really, really poor comprehension skills.

I came home from the conference with my head really, really full. Not only was the conference instructive as to how the Visualizing and Verbalizing process works, but we were all trained how to implement it (and yes, I was the only parent in the room among school teachers, reading specialists, speech paths, SPECS, administrators). The first day I went back to my hotel room and I thought, there is no way I could do this with J. By the end of the second day, I thought, “I could totally do this with J.”

Even though I had all the info (and the research made sense) I didn’t understand really what J did with language until I got a text message from my friend, A. We were texting about meeting up that day and she told me that she had to wait around for the fireplace guy to come.

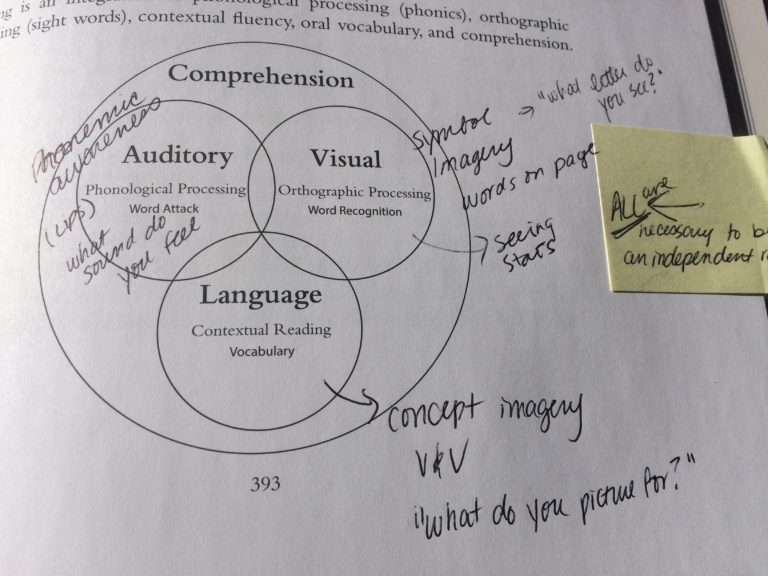

And immediately, I did what we all do without thinking about it. I didn’t realize we did this until the conference, but if you start paying attention, you’ll see that you do it too. I pictured my friend, A, in her living room, standing in front of the fireplace, waiting. It wasn’t a detailed picture—I didn’t see wood burning in the fireplace, I didn’t see her short blonde hair or decide if it was curly or straight that day. I didn’t even picture her clothes. But I had a composite picture of the situation. And from my conference I know that J doesn’t know how to do that with language.

Which had me thinking, how would J view that text. If he’s not making pictures with language, what is he doing with language? He “knows” all those words in the text. He can identify “guy” and “fireplace” and comprehends what those words mean.So how does he process language?

And then I started watching him, and have discovered how J uses and views language, and it’s the answer to all of his language problems. I’m not sure if anyone who has worked with him (including me) has seen it or made the connection. But here are my observations. And now everything makes sense.

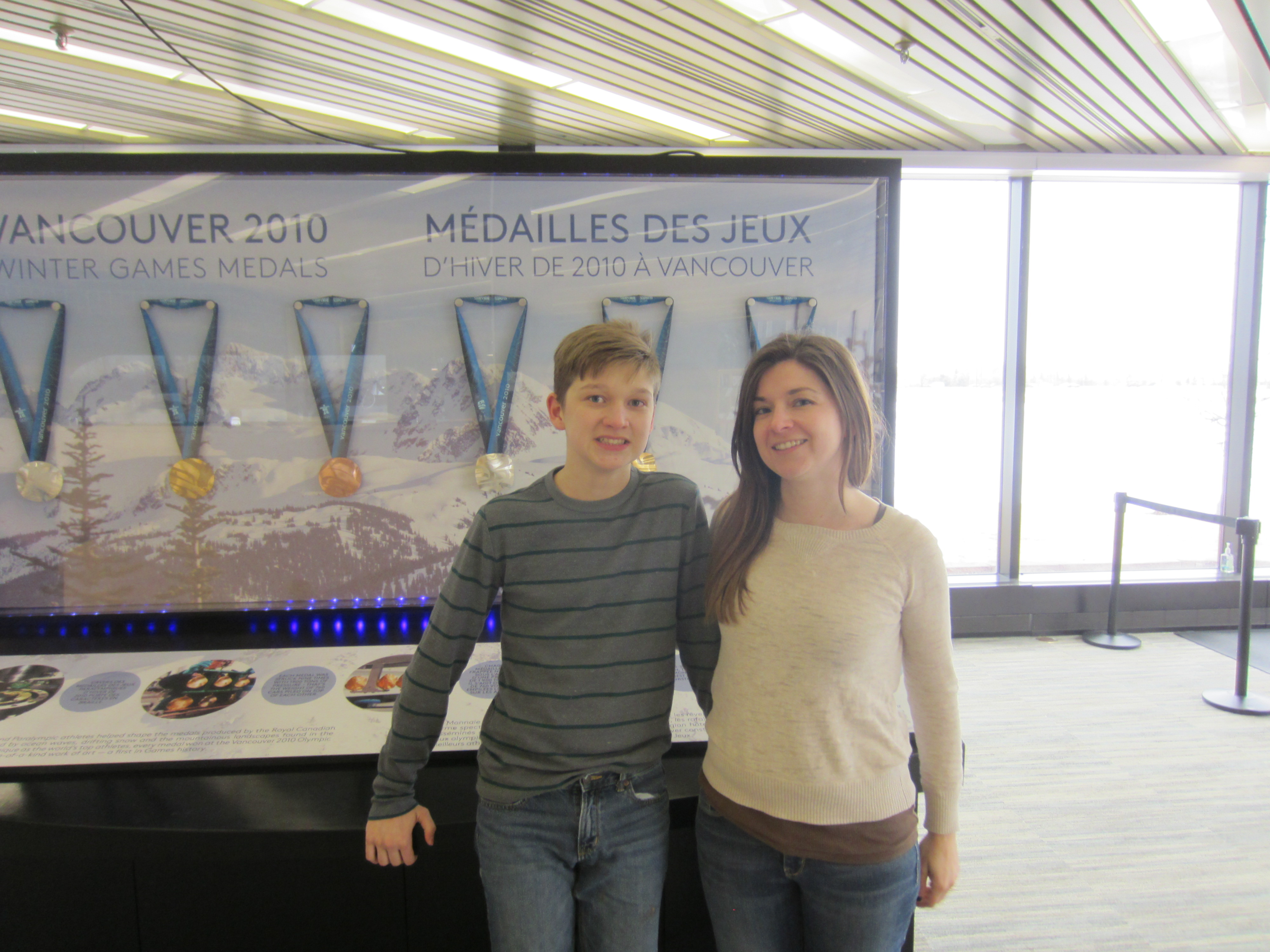

J, 4, showing off his spelling words. J struggled greatly with speech–he had been in speech therapy

for two years already at this point. The only time he would “talk” to me is if he were spelling

or “reading” out of a book.

1) J sees words almost exclusively as phonological puzzles. Since I was in Minneapolis, I (of course) made a trip to IKEA and came back with some assorted goods. I had left the packaging of a nightstand lamp on the kitchen counter, and J’s face immediately lit up and he asked, “KNUBBIG.” How do you say that? And he started sounding out the letters, trying to find the word phonetically. He did not ask me what the word meant. He just got excited about saying the word. And then he left the kitchen. This also explains his OCD relationship with words. He’s not paranoid about the representation of the words. He’s paranoid about word combinations. “RE-” words. “DE-” words. Words that start with certain sounds.

2) J seeds associates emotions with all words. He wants to know if words are good words or bad words. J asked me the other day about the phrase “calling the cops” (I think it’s a phrase in one of his songs on his Ipod). “It’s bad right?” he said. “It means you’re breaking the law and going to jail.” I explained to him my “picture” of calling the cops. “I picture someone talking on a telephone and a police officer on the other telephone—he’s wearing a blue button down shirt and a black hat and a gold badge—and the person talking on the phone is calling the police officer because they need help.” He answered. “Well that’s bad, right?” He does this with every new word he learns too. J will ask for the definition and immediately ask, “Is this a good or bad word.”

3) J uses language to elicit a reaction from someone else. J doesn’t use language to build stories or ideas with someone else. He uses it to get a reaction. Whether he’s spelling really long and obscure words to you, listing squares or cubes of numbers into the 10,000s, listing every exit in North Dakota, or asking your feelings about zits, all of his language interaction—ALL OF IT—is to get a pronounced reaction out of you. And that’s it.

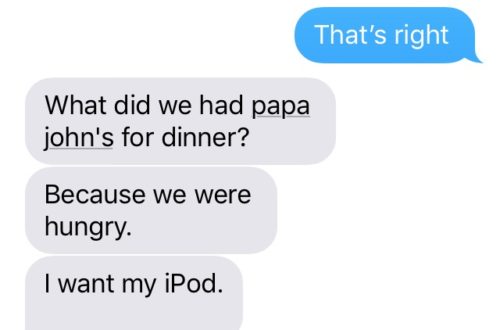

So when I look back at my friends text, watching how J interacts with language—knowing he isn’t making mental pictures or building stories—knowing that language means something very different to him than it does to the rest of us. This is (most likely) how J sees that message.

“This message is from A—I know A, she’s I’s mom, and she makes really good treats. I like I. I like it when A makes us cookies. She makes chocolate covered marshmallow eggs at Easter. I really like her house too. Fireplace. Fireplace is a compound word. Compound words are good. I know other compound words…”

All of a sudden, I understand where everything is going wrong. Why J’s reading comprehension is so poor, why he can’t answer people’s questions appropriately. Everything makes sense now. He isn’t looking at the words in the same way the rest of us are. He’s not wrong in his thinking—it’s just that nobody else uses language that way.

It’s enlightening and overwhelming. Now I know where the breakdown is happening. The good news is that there’s a learning process that can help him make those pictures (and there are many, many other kids that have this problem too). It’s a retraining of the brain to interact with language differently—which is awesome, because once J learns this way of thinking, he’ll be able to use this skill on a consistent basis. Like learning another language. It’s intensive because ideally J needs to spend 4 hours a day doing it for about 6 weeks. As in the words of the presenter, “If you’re trying to learn French, is 10 minutes a day going to cut it? Of course not. You need intensive practice daily.”

And that’s where the hard part comes in. It’s a grueling process—something I can do with J, and/or something I can pay someone else a lot—A VERY, VERY LARGE LOT—of money to do. But I know my J. Brain training is quite the battle. I saw it where he held his pee for almost 12 hours while potty-training. Just because he didn’t want to do it the “new way.” When we first started running, we ran every morning around the block while J screamed the entire time how much he hated it and me. And both times, right when I was ready to cave, J turned. I mean, the kid runs 4-6 miles a day and is begging me to go out and do it.

I know once we get through the resistance, he’d be able to do it.

It’s going to be a really, really interesting summer.

2 Comments

Edith Wall

Very interesting–I remember kids ,though my years of teaching , who could read any thing–excellent oral readers—and who understood very little and kids who could spell any word –spell words that they had no understanding of—. I never understood how that came to be . I always gave great credit to the primary teachers for such successful teaching of the” mechanic” of these skills to students who seemed to lack so much understanding of what they were doing and why. This sheds some light.

sarahwbeck

Thanks so much for reading Auntie Bano! I love to hear your teaching stories!