For Those of You Who are Wondering

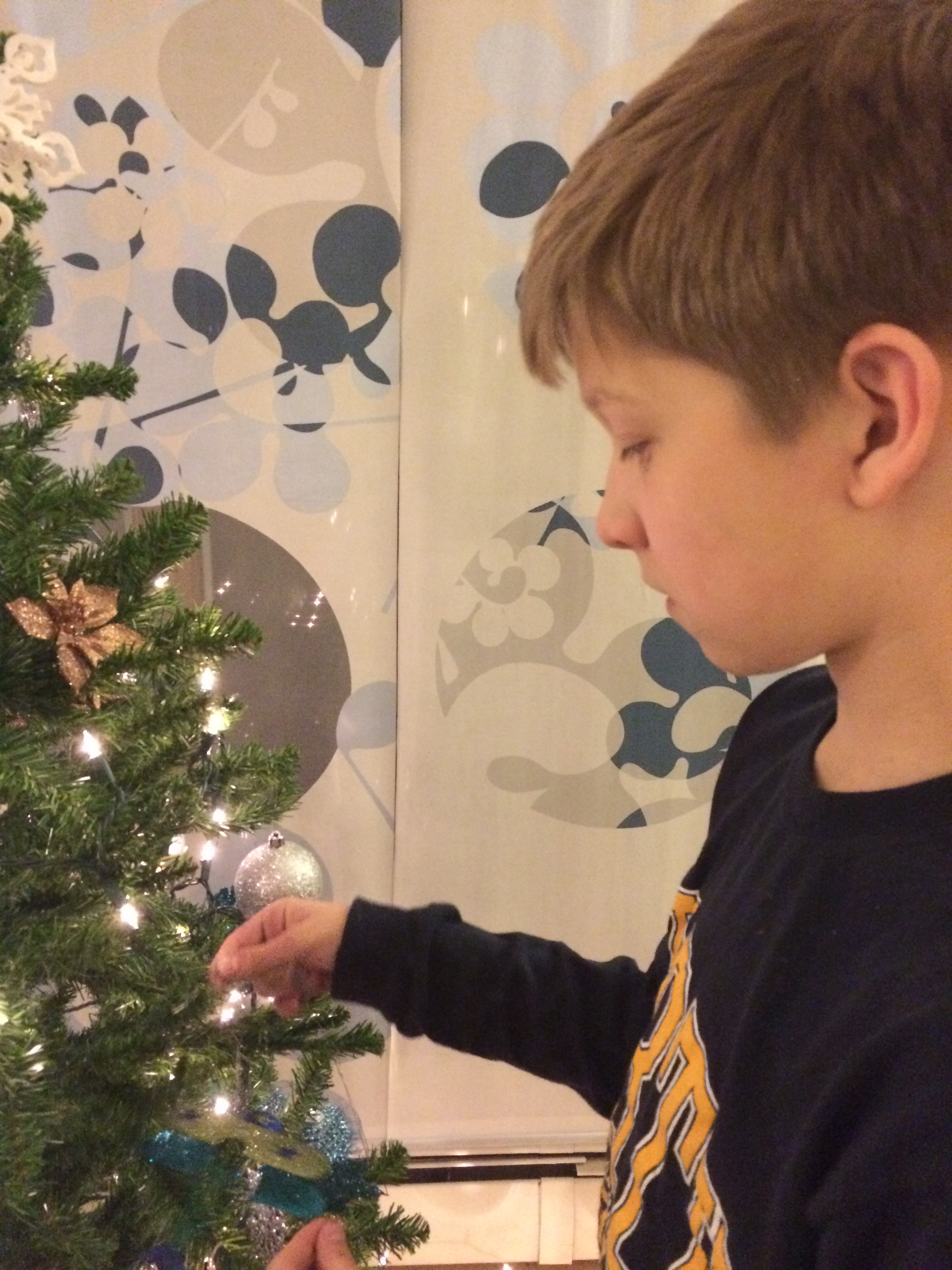

While reorganizing our home office over the last week or two, I found dozens of J’s IEPs and progress reports starting from preschool. I’ve been hoarding them like tax returns, not sure if I’m supposed to hold onto them, not sure if I’ll ever need to pull out an IEP from, say, 2008 or if any of that information is still useful. I’ve decided to keep those files for now, and maybe read through all of those reports again in preparation for J’s annual IEP in the next few weeks. J has made significant progress thanks to early intervention, but who knows—maybe there are some underlying trends that are still there in J, hidden away and morphed into something that looks different but still hasn’t been addressed or even resolved.

Among these stacks of papers, I did find something that belonged to W. On October 16, 2007, 37-month-old W was screened using the Denver II at J’s preschool where she was attending as a peer model. That’s right, back in 2007 I had a few concerns about W’s development and I had her screened right away, just like I did with J.

I didn’t want to take that chance. I didn’t want to “wait and see.” “Wait and see” is what friends and doctors told me when J was 18 months and couldn’t put two word sentences together and I’m sure glad I didn’t listen then. I don’t want to think of all the years of growth J would have missed without early intervention—if we had entered kindergarten from scratch, if it had taken a few years after that to realize that he had autism. I had a gut feeling at 18 months that something was up—even if I couldn’t explain or articulate to people what that was.

I didn’t have that gut feeling with W. Not in any way whatsoever, but with the hours and hours I spent researching autism one thing did pop up again and again—that siblings of autistic children are more likely to be autistic than those who do not have an autistic sibling. That was back in the early 2000s. Research now suggests that trend is even stronger (see here and here)

I’d get that question a lot. Once people found out J had autism, the questions started about W. One time we were at the wading pool in Lawrence—at an autism playgroup—and almost every parent came up to me asking, “Does your daughter have autism too?” When I answered, “No,” they’d continue with either, “Wow! That’s amazing” or “Wow, you’re so lucky. Look at her—she’s such a good playmate for your son with autism.” That’s when I realized that almost everyone at that little playgroup had more than one son/daughter on the spectrum.

Of course that little playgroup is a poor sample group. The frequency isn’t THAT high for multiple children with autism in a family, but between experiences like that and the research I decided that I wasn’t going to chance it with W. Right around 3 ½ I noticed when I asked her a question like, “W, do you want milk or juice to drink?” W would answer something like, “The dolphins and unicorns like swimming together.” Answers that had had nothing to do with the questions I asked. I talked to her preschool teachers and the speech therapist in the classroom, and while they noticed random answers like that too, and while they didn’t think anything was wrong they told me, “We are totally up for a screening if that’s what you want.”

Deep down I was pretty sure that she didn’t have autism. But I wanted to rule it out—after all, there was some funky speech going on, so on October 16, 2007, W was screened by the early intervention preschool using the Denver II (the Denver II has fallen out of favor as a screening test for many early intervention programs—many use different testing now, but this is what was used on her in 2007).

Here’s the summary of the report:

Results: Suspect

Denver was Suspect due to one delay, brush teeth with help and one caution, put on a t-shirt without help. Keep working with W on “self-help” activities like getting dressed, brushing teeth, washing hands, etc. For fine motor development, you can start showing W how to draw faces and shapes. For large motor development, you can show her how to hop and continue working on balancing on one foot. W was advanced in this area! For language, ask W open-ended question frequently and try to engage her in short conversations. Ask her to define words and show her what the different prepositions mean (over, under, on top of, beside, etc). No concerns at this time! Keep up the good work!

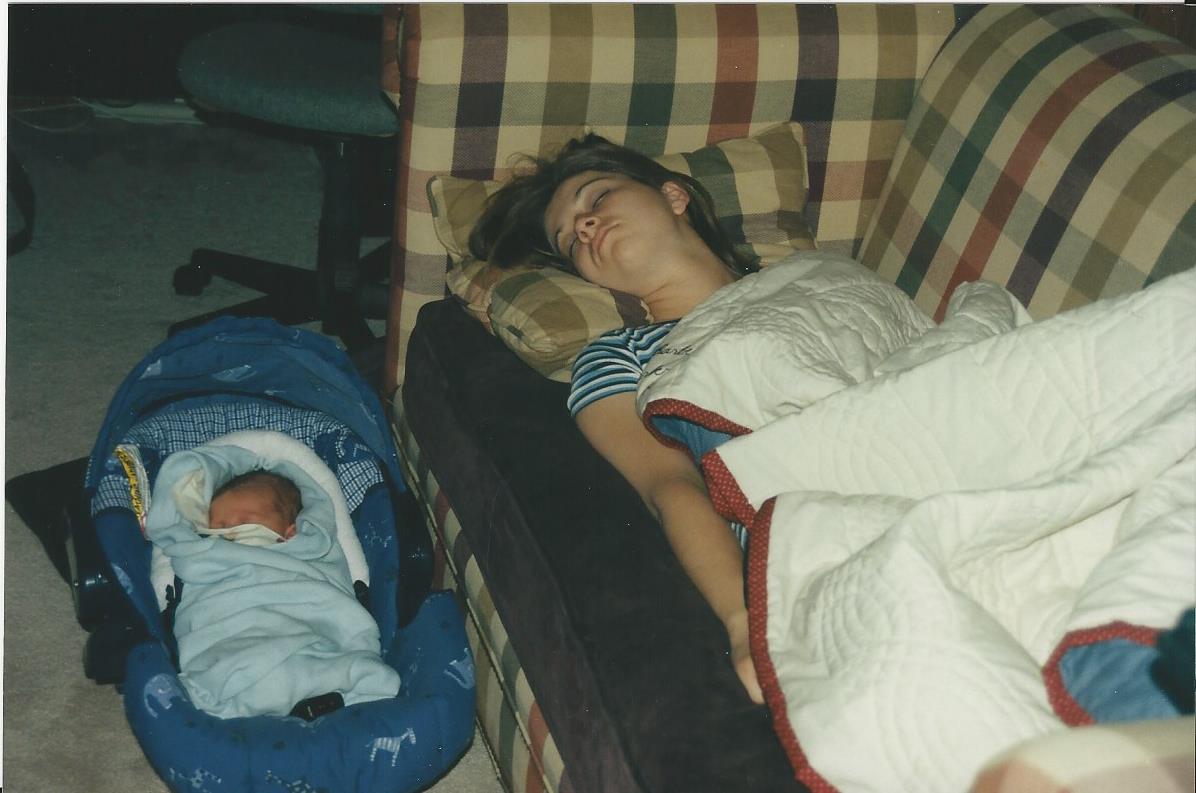

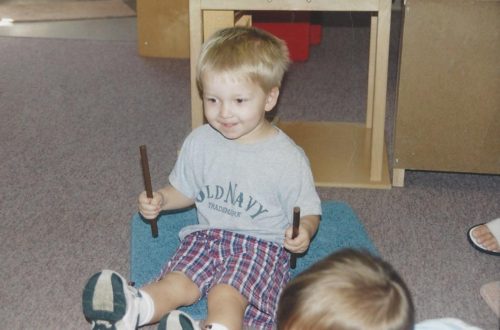

Brushing teeth? Self-dressing? These things weren’t even on my radar. And for good reason—she was only slightly behind in these areas. W had no speech or cognitive delays, but W’s dressing delays came because I was always struggling with J, trying to get the door with an autistic toddler can be quite the challenge, and when the baby sister is only 22 months younger is lagging behind, you sometimes just do things for her. At that point in my life, it felt like I had twins and one especially needy twin at that.

The screening was a good reminder—that even though W had no significant delays, I did need to make sure she wasn’t neglected because of J. On top of being enrolled as a peer model in J’s early intervention preschool, we enrolled in the Parents as Teachers program (a program where a developmental specialist comes to your house and shows you really fun games, books, and activities to do with your child and helps you understand how to support development as a parent). I needed those things. I struggled a lot as a mom of little kids. I needed a village to help me raise not only J, but W too. Other people can see things you don’t. Other people come up with ideas you’ve never thought of before. And it’s really helpful.

Every few months, without fail, someone comes up to me with concerns they have about their child’s development. Most of the time they’ll tell me the quirky things they see their child doing and then comes the question: “Do you think I should get my child tested? The doctor says it’s nothing, but I’m not sure.” They’re always hesitant—I’m not sure if they’re scared to find out something is wrong with their child, that their child will be labelled, if they’ll have to put their child on meds, that the results will forever change the way they look at their child…Mama and Papa bear brains go to worst case scenario modes quickly.

But for me, I feel very, VERY strongly about developmental screenings. SCREEN. If there’s a delay, then great! You know what’s going on and what to do next. If there’s no delay? Great! You know you don’t have to worry anymore. No harm, no foul, right?

It still upsets me that as a society we feel that it’s a no-brainer to take your kid to the ER in the middle of the night because your child has a fever—even if you’re not sure it qualifies for the “high fever” category, but as a society we are willing to sit for months, even years to make decisions on a child’s social/mental/emotional development. I get it, the word “development” implies growth and change, but at the same time there are baselines in development that every child should be making at different points in their life. I feel like this hesitation is very similar to our hesitation to talk about mental illness—it’s something we can’t get lab results on, and if we can’t get the lab results on it, then maybe, maybe it’s not “really” real.

When people ask me about screenings, I tell them the stories of both J and W. One time I was right, the other time I was wrong, but I never for a minute regret screening them at the age I did. We test our kids umpteen times a semester for academic purposes once they hit public school age. We take our babies for well-child visits every year to measure their skull sizes and weight gains and growth spurts until they’re teens and then some.

Why are we so scared of assessing the social-emotional-mental development of our children?