Butterfly Endings

This essay was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue of Chaleur Magazine.

Butterfly Endings

She stood over the crib, looking down at the baby—wrinkles and rolls, chubby thighs, round toes—resisting the urge to touch him. His chest rose and fell steadily, his lips pursed in a pout. He was sweaty in the summer night. His blond, fluffy hair now lay wet and matted around his ears and the nape of his neck. He sucked in a few short breaths, and then blew out a slow, even exhale, his chest rising and falling in rhythm again.

“This is not my baby,” she smiled to herself. “He’s perfection.”

He’ll be a football player, she mused. Or baseball player. He would play the cello. She looked at his fat hands and fingers, slightly curled, and imagined them placed around the long, dark neck of the instrument, the other hand lightly balancing a bow, gliding it across the bridge. He would be smart. He would cure cancer.

After all, he was perfection.

He was a smiley baby, always smiling at her, a big, gummy, toothless smile, blue eyes studying her face. “What a beautiful baby,” people would say as she pushed him along in the stroller. “Love those chubby thighs,” they would say. He crawled at nine months. Said, “Mama, Dada, and Bu-bye,” at thirteen months. Walked at fourteen months.

At fifteen months he tiptoed.

Ever so often he would tip-toe. After toddling across the shag carpet and stumbling over the threshold where the carpet met the grey-tiled kitchen, he would tip-toe. Soft toes squished against the stone floor, his meaty feet arched up high, his diaper sagging. She smiled. What a cute little boy she thought.

They were inseparable. She taught him things. She played with him. She read to him. He loved The Very Hungry Caterpillar, his fingers poking through the round holes of the apple, pears, plums, strawberries, oranges, Saturday’s feast and Sunday’s leaf. He loved the butterfly ending. They would read it over and over again.

He loved to spin things.

They would spin all sorts of things together. Tops, saucers, coasters—he loved coasters. Coasters quivering and trembling. He would giggle and giggle, begging for more.

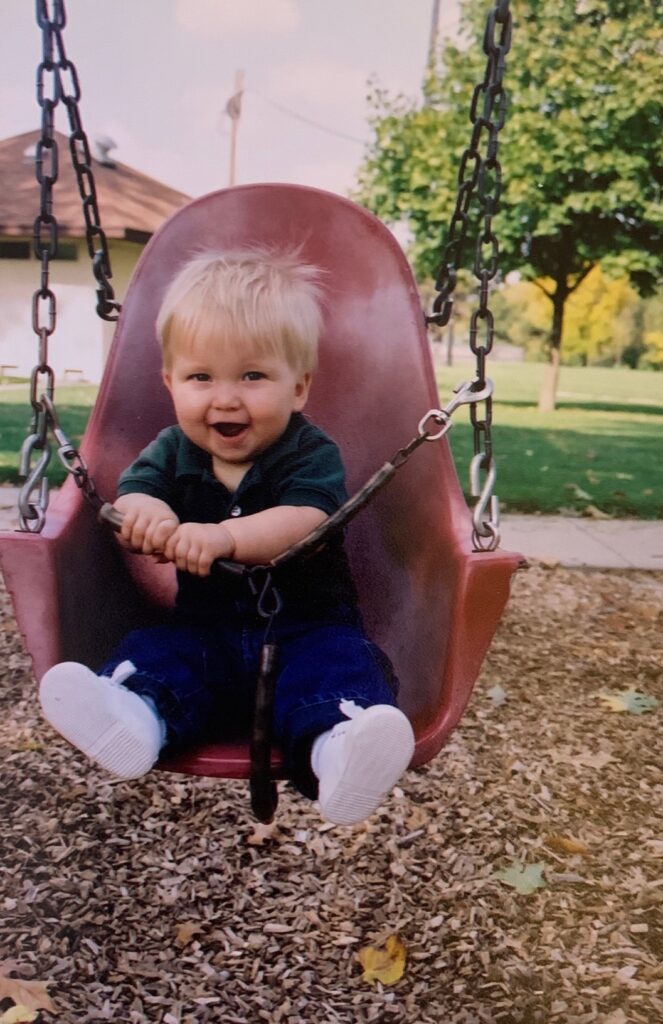

They would go to the park together. They would bake under the summer sun or shiver in the gusty fall chill. He loved the swings, his chubby legs dangling, his fat little hands clinging to the chains, his fluffy hair blowing in the breeze. She would push him over and over again, watching the Junior High girls congregate afterschool, squealing at the top of the slide, “I can’t believe you kissed him!” the tall, red-haired girl laughed hysterically, jumping up and down, flapping her hands with excitement. Soon the gaggle joined in, jumping feet, flapping hands. It was as if they could fly.

When he was excited—when he played his spinning games—her little bird flapped his dimpled hands too.

Then one day she noticed something. He no longer said, “Mama, Dada, and Bu-bye,” like he did at 13 months. He wasn’t learning new words.

But he tip-toed.

He no longer wanted to play with her, at least not like he used to. He craved spinning things. He would just go off, alone, to spin. “He’s gaining his independence,” she thought. “He’s about that age.”

He had tantrums.

“He’s about that age,” she told friends. “He’s gaining his independence,” she reassured herself.

But every night while brushing her teeth, a feeling would creep in, the feeling that something wasn’t right.

He no longer looked at people.

Then one day something happened at the grocery store. He screamed. Primal screams. She tried picking him up off the floor—people were staring—she tried picking him up. He was a dead-weight in her arms—a squirming wet fish. His body arched back, his pot belly pushed out. She hobbled out of the store, grocery bags strapped around her arms, and wrists. Around her legs a wailing toddler pulled on her jeans, his body dragging across the parking lot. People stared. She managed to get him in the car. He was pulling her hair and clawing at her face drawing blood as she struggled to buckle him in the car seat. He was crying. She was crying. Something was wrong.

She sat in the driver’s seat and cried.

“This is not my baby.”

The psychologist with dark eyes closed the door, separating her from her toddler. In the next room, he was making happy sounds, lining up blocks in a perfect, straight row. He was always good at that. Lining up objects, making sure everything was in its place. They had performed tests on him in that room. “My baby’s good at things,” she told them. But the woman wanted to talk to her alone:

“Classic signs of autism: loss of eye contact, speech delays, rigid routines, limited interests…” The woman followed down the list with a perfectly sharpened pencil pointing out deficits, impairments, and difficulties. The woman was clinical and efficient.

That night she stood over his bed, looking down at the toddler—wrinkles and rolls, chubby thighs, round toes—resisting the urge to touch him. His chest rose and fell steadily, his lips pursed in a pout. He was sweaty in in the summer night. His blond, fluffy hair now lay wet and matted around his ears and the nape of his neck. He sucked in a few short breaths, and then blew out a slow, even exhale, his chest rising and falling in rhythm again.

The tip-toeing, the spinning, the flapping.

No more Mama, Dada. No more Bu-byes.

No more blue round eyes.

She thought of butterfly endings.

Looking down at him, she whispered into the silence, “This is not my baby.”

2 Comments

Alli

Wow! This was really beautiful and heart breaking. I’ve been a silent reader for awhile but this piece was far too moving to not comment. Thank you for sharing!

sarahwbeck

Thanks for your kind words and thank you for reading 🙂