Ape Brains and the Middle School Boy

Because we walk after school from the middle school to the high school every day, I’m getting a refresher of what the real middle school population looks like. Not the one that you see in the halls, following school rules, responsibly exchanging books from their lockers to be prepared for the next class. The population who is headed home from a long day of school, letting out that bottled energy, true colors showing. The pushing, shoving, jeering, girl flirting kind of middle school population.

More specifically, the ape-brain middle school boy population.

Like the kid who pushes 30 miles an hour on his moped, circling the block a few times to impress the girls walking home. The boy chasing after the moped, flip-flops smacking against the road while his friends walking behind on the sidewalk wail and cheer after him, also trying to impress the girls walking home.

J watched this whole scenario go down the other day and said to me, very loudly and proudly because he’s great at judging other people’s bad behaviors, “That’s really dangerous. They’re engaging in risk behaviors.”

Risk behaviors: Actions of choices that may cause injury or harm to you or others. One of many terms in Chapter 1 grade 7 Teen Health we’ve been practicing since school started. Along with consequences, cumulative risk, prevention, self-evaluation. Every kid in grade 7 health has been learning these terms since school started. Because apparently for the human brain to progress, it has to digress.

And for some reason boys seem to most visibly manifest the digression to the ape brain.

My sister reminds me of this all the time. She should know. She taught junior high art for a few years. She’s told me stories of boys–neurotypical boys doing really stupid things. A “normal” boy slithering on his stomach into her art classroom, claiming he was a snake. The boy who thought it would be really funny to set off a stink bomb but failed to think that setting it off right next to him would 1) ensure he was the victim of the most potent part of the bomb and 2) would pretty much let everyone know that he was the perpetrator. The boy who showed up in a fur coat every single day of the year. My sister’s stories trigger memories I have of middle school behavior. Like when I was in junior high and heard that a boy in another homeroom took a pair of scissors to a girl’s ponytail sitting in front of him.

During J’s ultrasound and the “reveal” of the little turtle between his legs all I could think of was what boys looked like in middle school. I knew nothing about boys. I grew up with one sister. I had no idea what to do with boys. Especially when they turned into boys like that.

I’m pretty sure J had an ape brain day today, full of defiance, work-avoidance, attention seeking, pushing the limits. At least, that’s what my gut told me today when I picked him up after school, “This is it. This is definitely a middle school boy pushing the limits exhibiting full risk behaviors.” But with J it’s tough. I can’t always be 100% sure. Not all “behavior” days look the same. Last week’s spectacle looked different. Last week, my gut said, “This isn’t middle school boy. This is something else.” It didn’t feel like middle school boy. I can’t even say for sure if it even looked like autism boy, because sometimes I suspect there are other things going on we don’t even know about.

So while there are rules and protocol to follow for the typical testing-the-limits middle school boy, there are no rules and protocol for dealing with the autistic testing-the-limits middle school boy. Because here’s the fun thing about autism: autism looks different in every kid. And to make matters worse, it very, rarely stands alone. It’s got friends like anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and more that look a lot alike and like to hang out with each other. It’s what leaves us parents, teachers, and caregivers banging our heads against the wall. Trying to figure out what to do.

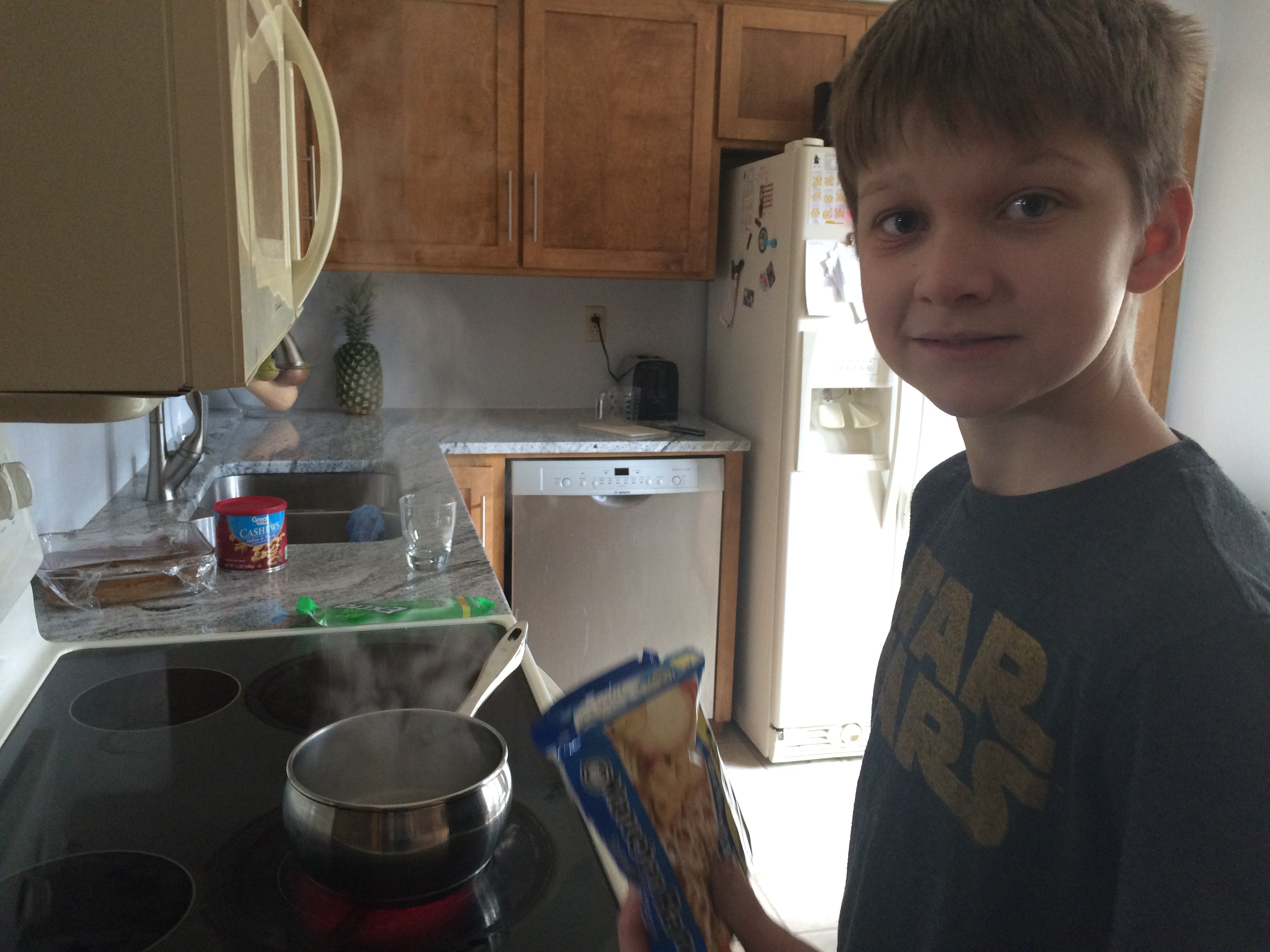

Steve and I escorted J home after school angry and demoralized. J knew the drill. Late dinner minutes. Privileges taken away. But when he got through the door, he started to panic. “I need to go exercise.” We had already said no to cross-country. That’s a privilege. He has to behave to go. But he got more panicky and insisted. “I need to go exercise now. I need to get all this bad energy out.”

So we rushed to get changed and were able to get out of the door by 4. Steve drove us and we were lucky enough to hop out of the car and catch the boys at the intersection by the high school. Today was a hard practice. We ran drills. We ran far. J started crying quietly to himself near the end. He kept muttering, “This is hard but I can do it.”

I’m still not sure if letting J do cross-country today was the right thing. It is a privilege. He has to behave to go. But at the same time it seemed like he needed it. He seemed to know himself well enough to need it.

I’m not sure what we can do for now because I feel like we’re sort of spinning in circles. We need to find out if it’s the middle school boy kicking in, amped up anxiety that’s looking a whole lot different than it did a few months ago, autism that’s looking different now that he’s getting older, something new altogether, or some or all of the above. Unfortunately all of this takes trial and error and time. For the doctors to figure things out. For the teachers to figure things out. For Steve and I to figure things out.

Tomorrow’s a new day. We’ll see what happens.