My Black is Your Navy

For as long as I can remember, my dad has struggled with colour. I remember him rushing out the door to get to work, asking my mom one last time, “is this shirt blue or grey?’ or “does this shirt match this tie?”

There were a lot of questions about socks too. “Are these socks black or navy?” and the guaranteed followup question: “Are you sure they’re navy? They look black to me.”

My dad is red green colourblind, but he also has a hard time sorting out cool greens and light greys; light blues and light greys, light pink and light greys, brown and greens. When he was dating my mom in grade thirteen (the last year of high school in Ontario at that time), he painted a portrait of her using a photo and painted her eyes green instead of brown. When he gave it to her, she said she really liked it, but told him “my eyes are brown, not green.”

There’s a physiological reason that explains our differences in colour perception. Each of us has rods and cones in the back of our eyes, close to the optic nerve, to help us see colour. But some people are born missing rods and cones, or they don’t work right. Those people see a whole different colour scheme. They’re experiencing the world in a slightly different way. You and I can literally look at an apple, decide that it’s red, but might unknowingly be seeing very different types of red–maybe to me it’s more of an orange-red and to you it’s more of a pink-red. I guess when it comes right down to it, it doesn’t matter that we are seeing different shades of red. If we can both decide the apple is red, that’s close enough. We are both operating in the same world. We can understand each other.

Most of the time, I’m pretty sure J and me are not operating in the same world. J’s been going to visual therapy once a week and I know there are things he just doesn’t see the same way as the rest of us. I just sometimes forget it. A lot. About a month ago, J came through the door after a bike ride with a bloody knee and arm and the handlebars of his bike twisted to one side. When I asked him what happened he told me he biked into a tree. I automatically assumed that J wasn’t paying attention (he does have an ADHD diagnosis along with his autism AND he has run into trees before and once even a parked car), but when I was relaying that story to a friend, they told me that their kid (who had also gone through visual therapy) used to ride their bike into things all the time. It was because their kid had no depth perception. And that’s when the light bulb went off in my head. “That’s right, when J was assessed, they told us he had less than 5% depth perception–which is close to no depth perception at all.” J probably was paying attention. He just couldn’t judge how close or far away the tree was in front of him.

The last few weeks have been really revealing in how much J struggles with “seeing” homework. In fact, J is probably the only kid in his class who can’t see the same things the rest of his peers see, or sees something completely different altogether. Math it the subject where this always is the most apparent. We’ve been trying to make better accommodations for J’s assignments, and just by a weird fluke, I was able to discover some more ways that might make J’s life a little easier in some ways.

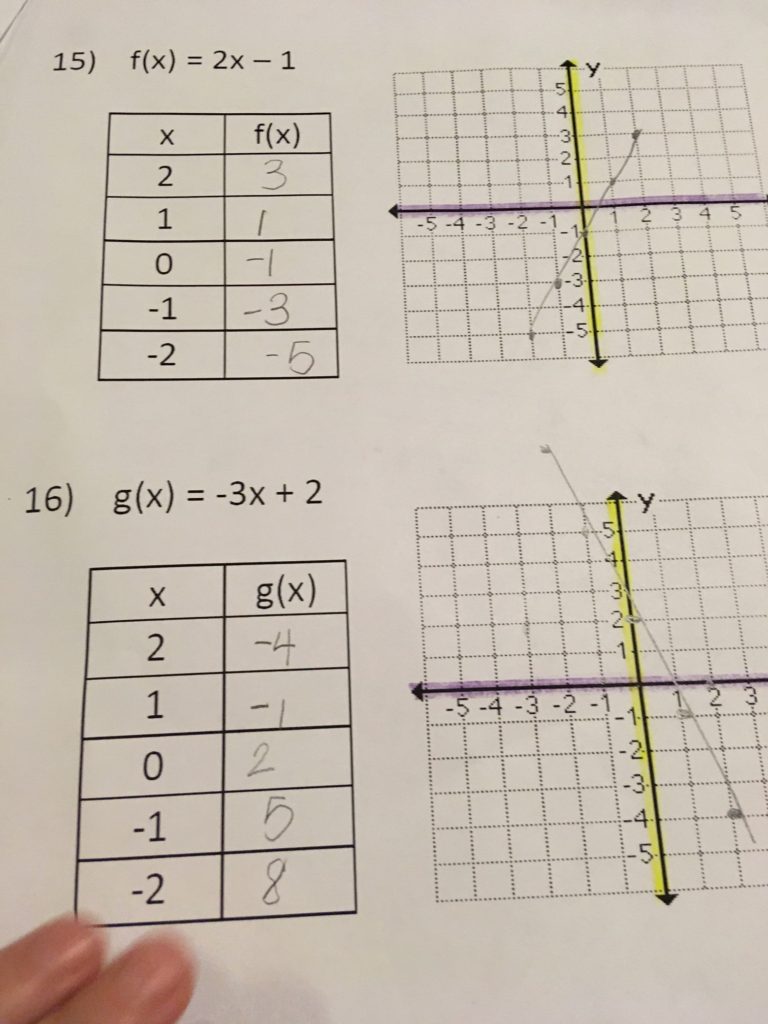

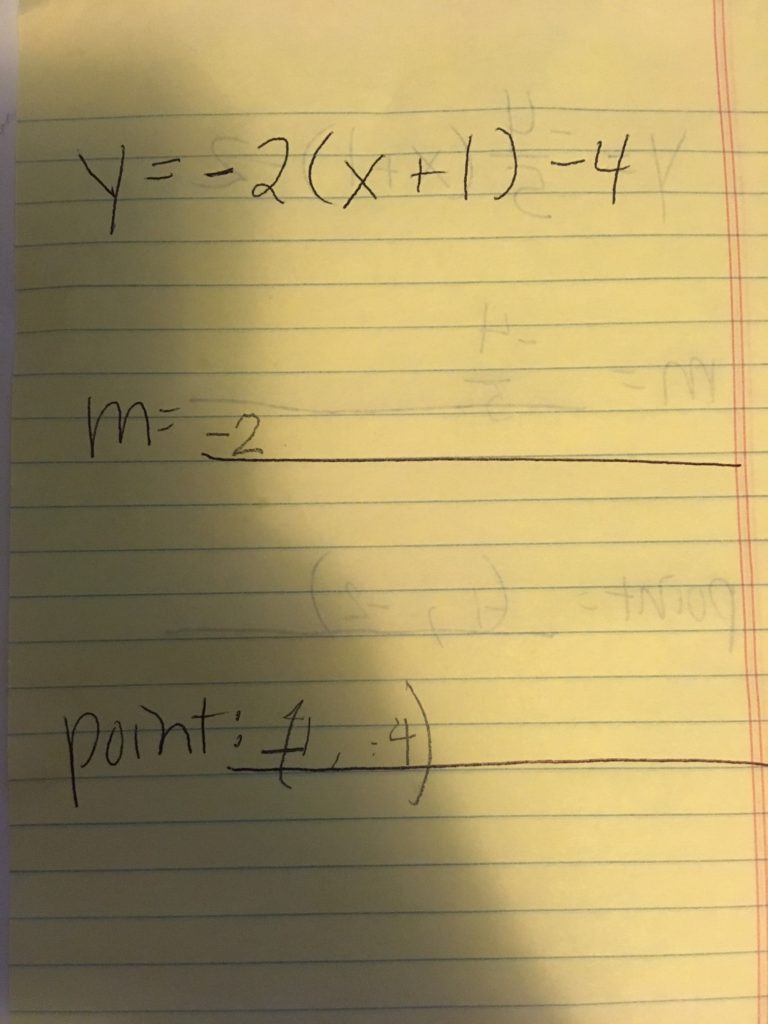

J’s teacher made HUGE graphs for him to graph on (because seeing a point and lining up things on multiple lines on an itty bitty graph is nearly impossible for J). But because the graphs ended up so big, so did the equations. There were only 2 questions per page and guess what? Not only did the graphing improve, but suddenly substituting each number into X became a million times easier too.

So for all of J’s homework assignments of the past couple of weeks, I made each question obnoxiously big–1 question per page, and suddenly J was finally understanding what he needed to do for every single problem.

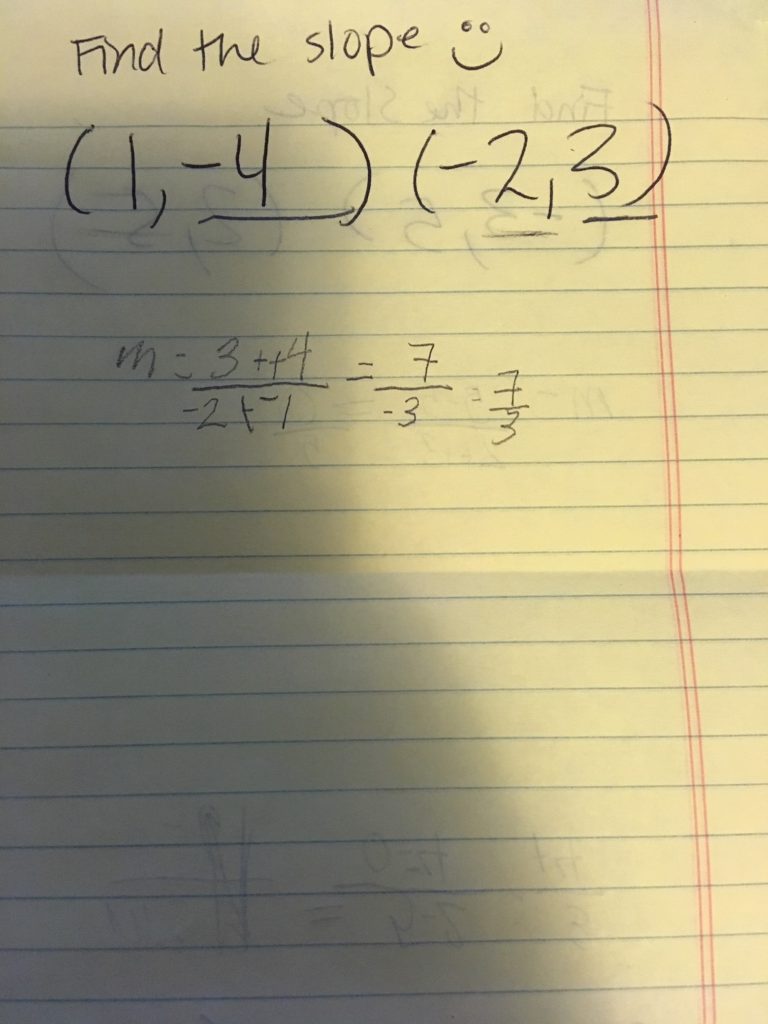

The next assignment didn’t involve graphing, and we went back to trying to work from a “normal” sized worksheet with 6 different problems on the page (because I thought, hey, J can see “normal” sized equations just fine). We started working with question 1, substituting numbers in for the slope and the y point and I asked J what number he needed to substitute for the x point and he answered “15.” Which was absolutely wrong. There was no number “15” in the equation we were working on. In fact, when I told him that the number was wrong and he needed to try again but he came up with another, random wrong number. To me it was obvious that he wasn’t paying attention–and didn’t want to be doing the assignment at all. He then went back to insisting that 15 be substituted for x and by this time, we were both pretty frustrated. “There is no number 15. Show me where you see the number 15” in a sarcastic tone. Sure enough, he pointed to a number 15–in question number six. NOT question number one. We weren’t even looking at the same equation. Somewhere, in the back and forth of substituting numbers into letters in the equation, J lost his place and was taking numbers from question 6 instead of 1. We were both looking at the same page, just not at the same spot. It was just like my dad’s colour blindness. J thought the socks were navy, I said they were black.

To me, it’s amazing that after all I know about autism, that after all I know about J’s autism and learning disabilities, there are still things I don’t catch just because I see the world, the assignment, the situation in a certain way–the way most of us see it, and just make the assumption J sees it in the exact same way too. You would think I would know better by now. But that’s the strange thing about a special needs kid who has adapted and adjusted pretty well over the past few years. Those struggles camouflage themselves really well. With this second time around with Algebra, I can see that light bulb of recognition happening of “I’ve seen this before, and I remember doing that.” He can work through the multiple steps of the algebra. So long as during that eye movement he doesn’t get lost on the page. He kept saying 15 because that’s where he really was. I thought he was just guessing random numbers because he never communicated to me that he was looking at question 6. It was just like the bike incident. When J came home from the bike/tree encounter, he kept apologizing for busting up his bike and running into the tree. He never told me that he couldn’t see where it was at.

I think that trying to see where your kid is coming from has got to be one (of many) hard parts of parenting. It’s easy as an adult to see your kid and know what they are capable of, and when they don’t respond in the way you know they should or how you think they are capable of acting to just assume they’re screwing around, not paying attention, or being lazy. It’s really hard for me to remember that my black might be J’s navy and that he might not fully understand or see what I see.

So I guess we’ll just keep on plugging at it until we figure out how to be on the same page.