Sabre-toothed Tigers

I’ve debated over and over again how to talk to my kids about school shootings. I’ve had short, infrequent, conversations with my daughter, who at this point, is totally unfazed by them. She tells me that she knows what to do–hide in place, fight back, almost with a defiant composure. She’s pretty confident in her self-preservation skills. I let her keep that confidence, even though, as demonstrated by February 14th’s events, when a school follows these procedures to a T, 17 people still die. Dozens are injured.

I’ve debated over and over again how to talk to my kids about school shootings. I’ve had short, infrequent, conversations with my daughter, who at this point, is totally unfazed by them. She tells me that she knows what to do–hide in place, fight back, almost with a defiant composure. She’s pretty confident in her self-preservation skills. I let her keep that confidence, even though, as demonstrated by February 14th’s events, when a school follows these procedures to a T, 17 people still die. Dozens are injured.

I don’t tell her the emperor has no clothes. False confidence is better than no faith.

And how do we talk to my autistic son about school shootings?

I don’t. And I pull him from any conversations that go into any detail about school shootings.

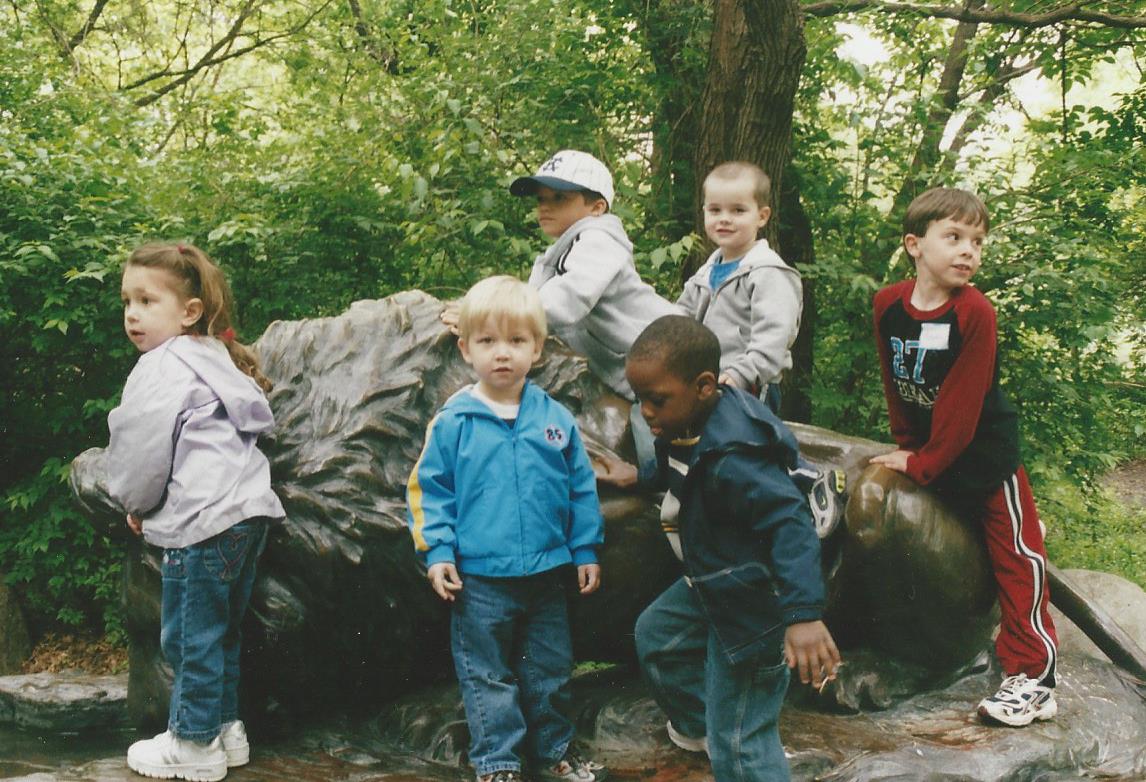

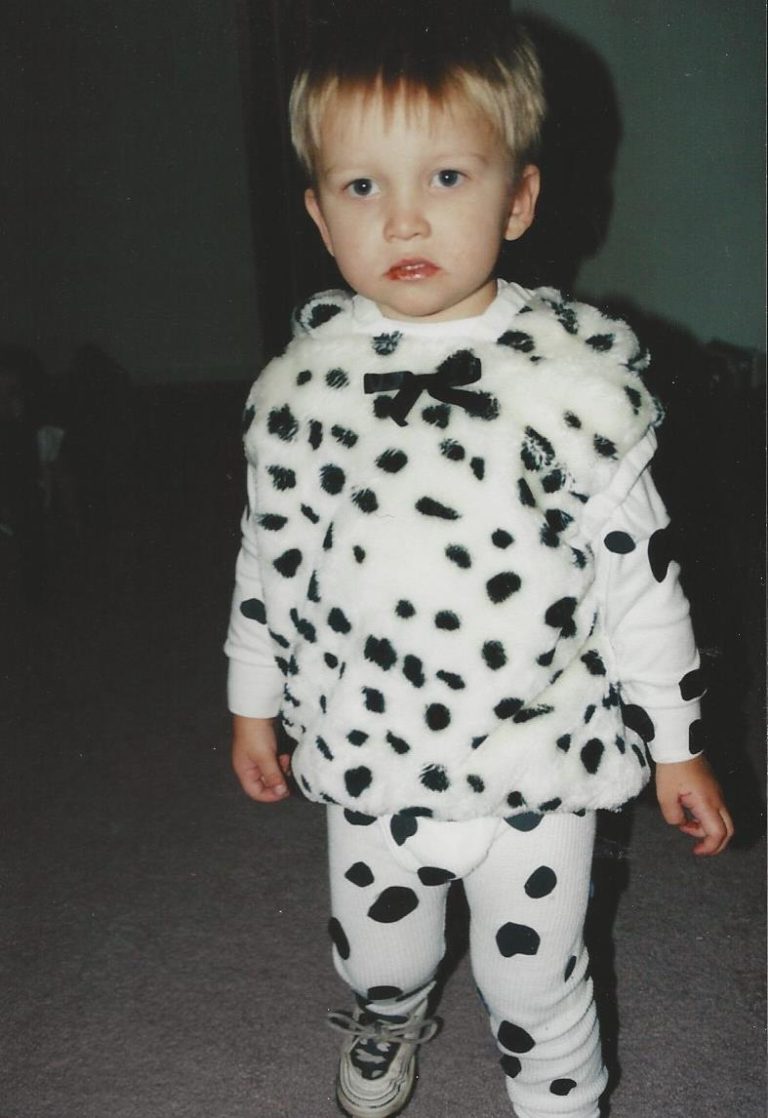

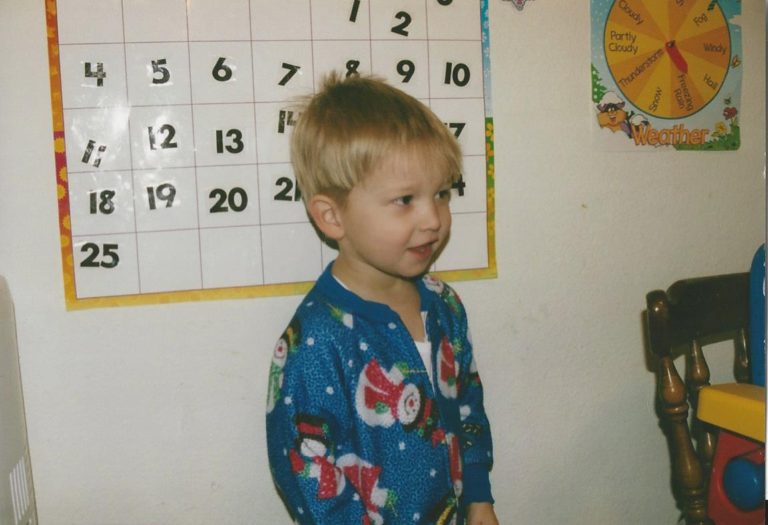

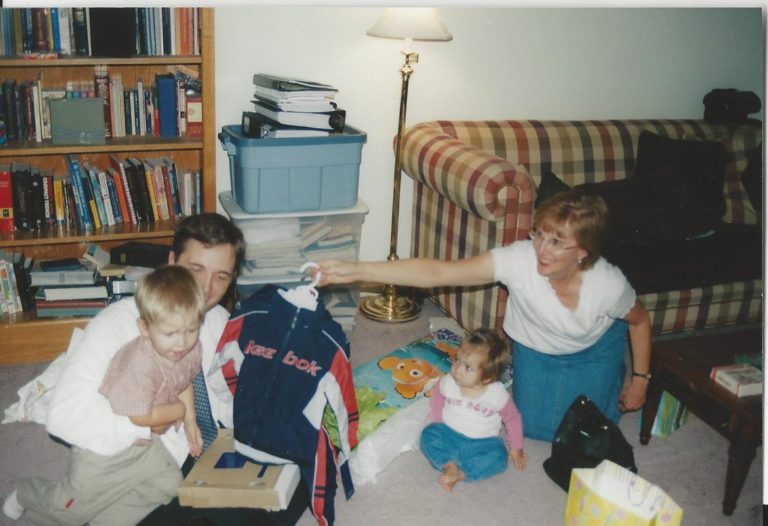

J was born with an inherent weariness, anxiety, and distrust of the world around him. He was a late walker, in part because he struggled with motor coordination, but in part because he was afraid to fall. As a toddler he was terrified of heights–climbing, sliding down a slide. The anxiety started really young.

He had panic attacks when he entered buildings–if he went through the wrong door or if the light switches were the “wrong” placement. If the room had light switches that had different circuits he would run around the room “fixing” them until they met the up/down pattern that felt right to him while making sure all of the lights stayed on or off.

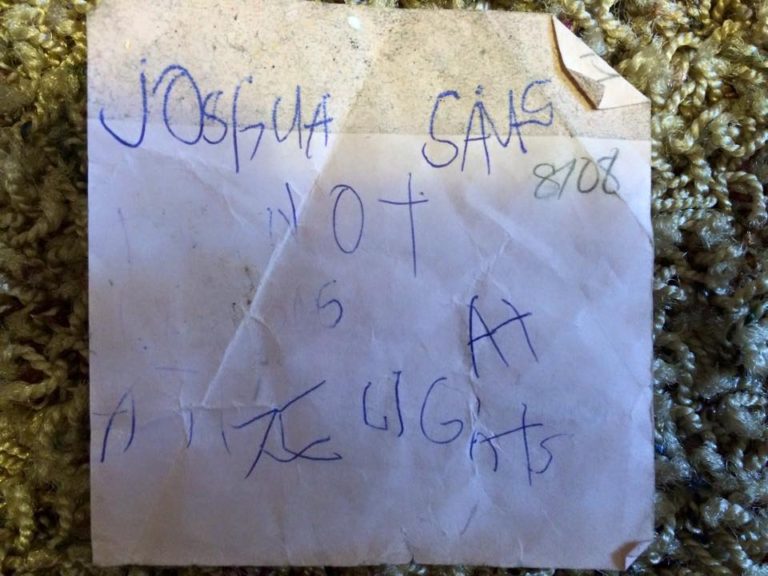

Numbers became triggers for anxiety. The number 50 took years to go over. Anything associated with the number 50: math problems that equaled 50, reading out of a book on page 50, house numbers with 50, interstate exits with the number 50, sent him into a heap of despair. He was six or seven years old when he started struggling with numbers.

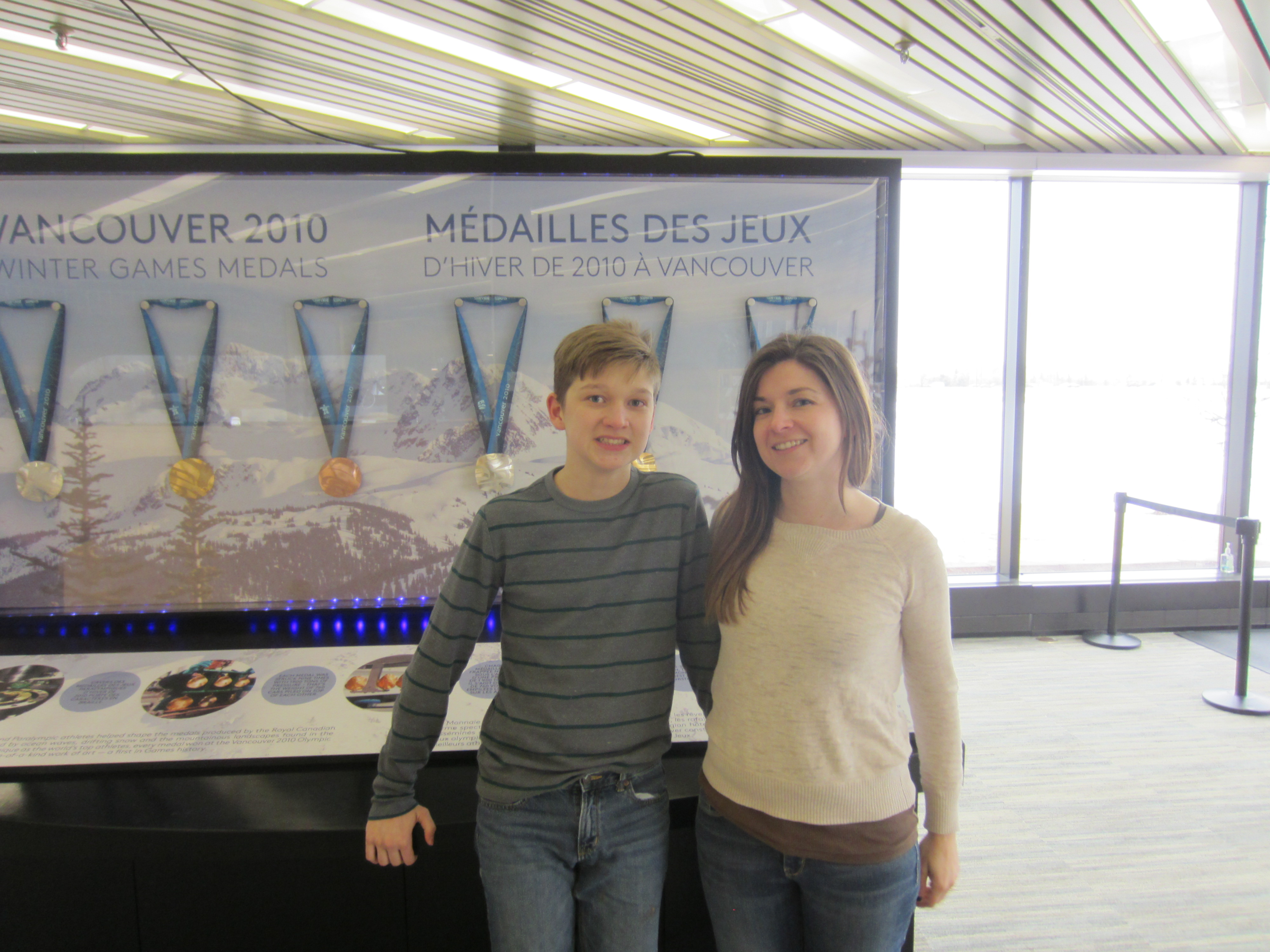

J startled very easily: dogs terrified him because they would bark or dart unexpectedly (which made things like walking to school or even Halloween) a huge struggle. Printers suddenly turning on in a classroom when a teacher wanted to print off an assignment would make him jump. Fire drills–we still struggle with fire drills–startle him. It’s the sudden sound, the sudden change of action and disruption of routine that stresses him out. Over the years of experience, patient teachers, therapy, therapy, and more therapy, he has overcome a lot of his fears and phobias. As I write this post, and think of all the old triggers and how they’ve literally disappeared I’m floored by the progress he’s made. He not only walks–he runs– and loves running. He’s overcome a lot of his phobias over heights: climbed mountains in Banff, Jasper (heck he even rode a gondola–held some internal fear inside but did it), and Rocky Mountain National Park.

He doesn’t get stuck on doors or light switches anymore. I haven’t heard a peep over “bad numbers” in months now. He’s grown a ton, learned coping strategies and has gotten better and better at consistently using them.

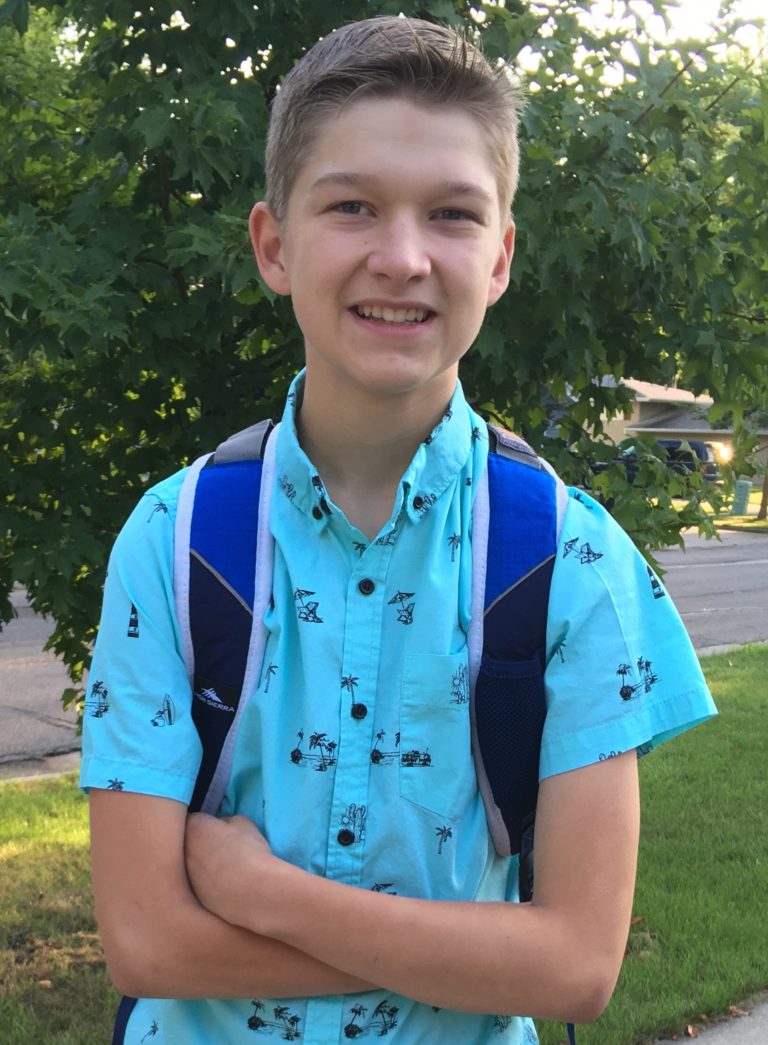

But there are still a few things that make him terrified–physically shake with fear. Fire drills. February 7 I got a phone call from J begging me to let him come home from school. He couldn’t concentrate in class, the fear of the fire drill going off was all consuming. He was convinced that the drill was going to happen that day. It was the first Wednesday of the month, and he had picked up that the last two fire drills happened on the first Wednesdays of the last two months. He saw a pattern forming, and was convinced it would happen that day.

I decided to go to school and try to convince him to stay (bringing him home and avoiding the trigger only makes the anxiety worse) so in single digit temperatures J and I walked around the perimeter of the school until his head was clear again and his body stopped shaking. He was able to go back to class (after we promised that there would be no fire drill that day) and finish the day. That was a HUGE victory.

The shooter in Florida pulled the fire alarm to cause extra chaos before he started firing.

So no. We don’t talk about school shootings. J would never set foot in a school again.

This latest shooting was really hard for me. They’re all hard, but this one was super hard. Maybe it was the fire drill connection? The extra panic the fire alarm caused? The fact that I can see how panicked my son would be in that situation? (J would be the first to die. His anxiety and need to escape would do him in). The fact that J is in high school now? The fact that it was after school pickup time, and I’m always in the school at after school pickup? The fact that a XC coach was killed? The fact that I feel so close to many of the teacher and students at J’s school because they are always so good and kind with him and the fact that so many teachers and students were killed?

My heart absolutely breaks for not only the victims, but the survivors–those survivors. 1 in 5 Americans suffers from mental illness already. Every single survivor, family member of a survivor, close friend of a survivor–their mental health has now been compromised. And mental health struggles are very real, very hard, daily struggles.

I think about all the kids on the autism spectrum at school (1 in 68 kids has autism today) who twitch at every unfamiliar or unexpected sound. I think about the kids at that school who struggle with anxiety in its myriad forms: The high functioning kids who are frantic for perfect scores on tests, the ones who worry about every pound they gain or every inch they grow (throwing up or starving themselves so they can reach a certain kind of perfection). The kids who hold their breath every time they check their social media accounts to see how many “likes” or “followers” they have. I think about the kids with depression, OCD, PTSD, survivors of sexual or physical abuse, and more, who have put on a brave face and put their very best into showing up at school for years, navigating their own doubts and fears. That’s at an average school in America. Now think of the crushing burden of having to deal with the aftermath of a school shooting.

We often think of anxiety and mental illness as just “crazy thinking,” but as humans we’re hard wired to default to this type of thinking. This type of thinking keeps us alert and safe. It keeps us from being eaten by sabre-toothed tigers. We have evolved to think this way for good reasons.

And I can play through all of the anxiety these students and survivors will encounter. Sabre-toothed tigers everywhere. I think of all of the ordinary things that could become triggers: Valentine’s Day, Wednesdays, the number 14, 2:19, 2:21. 2:28. Closets. School bells. Walmart. McDonald’s and more. The degree of each individual’s reaction will be different, but triggers still trigger.

A threatening incident conditions a protective response and no matter how hard you tell someone with anxiety, “you’re safe, nothing bad is going to happen, it’s just a faulty switch–an over-reactive switch in your brain…” they can’t hear you. We can tell those survivors those phrases, but they won’t hear us. Because they see threats in things that weren’t threats before. And their brain is just trying to help them survive. To stay alive. Fight or flight. No wonder so many of these kids are on TV rallying on TV for better protection of schools and gun reform. They’re in fight mode. They’re trying to stay alive. They want other kids to stay alive too.

Surprises–from the backfire of an engine to surprised birthday parties and unopened presents–the nature of surprise itself will be hard to navigate. Things like a printer or air conditioning, things most of us tune out, will suddenly turning on in an office or classroom. Anxiety hears them every single time. They will twitch and their hearts will race every single time until, time, therapy, and healing can help them cope through these things. Until they can recondition their thinking again.

At the same time dealing with the healing that needs to happen with the grief and loss of life too.

I don’t need to add school shootings to J’s arsenal of anxiety. He worries too much about the world as it is. Right now lockdown drills are the one type of drill he can handle fairly well because he doesn’t know what they’re for. He sees them as quiet time and as a break from class. And I’m happy to keep letting him think that way. A successful lockdown drill kept him calm through a tornado drill at after school pickup a few years ago. He doesn’t need to know that people sometimes come into schools and kill teachers and kids. He doesn’t need to know this is now happening on a fairly regular basis.

I’m so proud of how far he’s come–he has worked SO HARD to come so far. Let’s hope we can make it through the next 3 years (for J–4 years for W) without a shooter or some other traumatic event at school.

We’re still working (and hoping) that one day, he’ll finally be okay with fire drills.